Terms of Use

The Kindred Britain website is subject to Stanford University's standard Terms of Use.

These terms include a limited personal, non-exclusive, non-transferable license to access and use the site for personal, non-commercial use only. Please contact Nicholas Jenkins to request permission to use the Kindred Britain website and contents beyond the scope of the above license, including but not limited to republication to a group or republishing the website or parts of the website.

The Kindred Britain site may include hyperlinks to websites maintained or controlled by others. Kindred Britain and Stanford University Libraries are not responsible for and do not routinely screen, approve, review or endorse the contents of or use of any of the products or services that may be offered at these websites.

Acknowledgments

Kindred Britain is about a large network of people. And another significantly-sized network of people contributed to Kindred Britain’s building.

The three individuals principally involved in the creation of Kindred Britain are Nicholas Jenkins (Stanford University), Elijah Meeks (Stanford University) and Scott Murray (University of San Francisco).

- Nicholas Jenkins originated, researched and oversaw the Kindred Britain project

- Elijah Meeks was lead developer on the Kindred Britain site

- Scott Murray designed the Kindred Britain site

In addition, through the collaborative process, Jenkins, Meeks and Murray all contributed ideas, feedback and conceptualizations to the areas for which another person had primary responsibility. You can read their reflections on different aspects of Kindred Britain.

In grateful recognition of the essential parts played by colleagues, students, friends and family, Nicholas Jenkins, Elijah Meeks and Scott Murray thank the following individuals and organizations for their work, support and advice:

Primary Support

- Academic Computing,

Stanford University Libraries - Digital Library Systems and Services,

Stanford University Libraries - Digital Initiatives Group,

Stanford University Libraries

Writers, Editors, Advisers

- Hannah Abalos (Stanford ’15)

- Emma Townley-Smith (Stanford ’16)

Researcher

- Anthony Andrews (independent scholar)

Research Developer

- Karl Grossner (Stanford)

Other Technical Support

- David Chon (Stanford)

- Matthew Jockers (University of Nebraska, Lincoln)

- Wilson Restrepo (Stanford ’13)

- Jon Robertson (Stanford)

- Shilpa Thanawala (independent designer)

Logistical, Administrative and Communications Support and Advice

- Alyce Boster (Stanford)

- Corrie Goldman (Stanford)

- Martha Langill (Stanford)

- Nelia Peralta (Stanford)

- Emily Saidel (Stanford)

- Brian Thomas (Stanford)

- Makoto Tsuchitani (Stanford)

- Glenn Worthey (Stanford)

Other Funding, Infrastructural and Resources Support

- Office of the President of Stanford University

- Stanford Arts Institute

- Office of the Dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences, Stanford University

- Undergraduate Advising and Research, Office of the Vice-Provost for Undergraduate Education, Stanford University

- Office of Development, Stanford University

Informational Support

- Oxford University Press and the staff of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Indispensable Support of Many Other Kinds

- Eavan Boland (Stanford)

- Mimi Calter (Stanford)

- Zephyr Frank (Stanford)

- Stephen Hinton (Stanford)

- Richard Holeton (Stanford)

- Michael Keller (Stanford)

- David L. Kennedy (Stanford)

- Julie Lythcott-Haims (formerly, Stanford)

- Franco Moretti (Stanford)

- Alexander Nemerov (Stanford)

- Kathleen Quinn (Stanford)

- Aron Rodrigue (Stanford)

- Debra Satz (Stanford)

- Lauren Schoenthaler (Stanford)

- Matthew Tiews (Stanford)

- Robert Urstein (Stanford)

- Jennifer Widom (Stanford)

Familial Support

- Siri Huntoon

- Hugo Jenkins

- Owen Jenkins

- Hajra Meeks

Frequently Asked Questions

Overview

Navigation

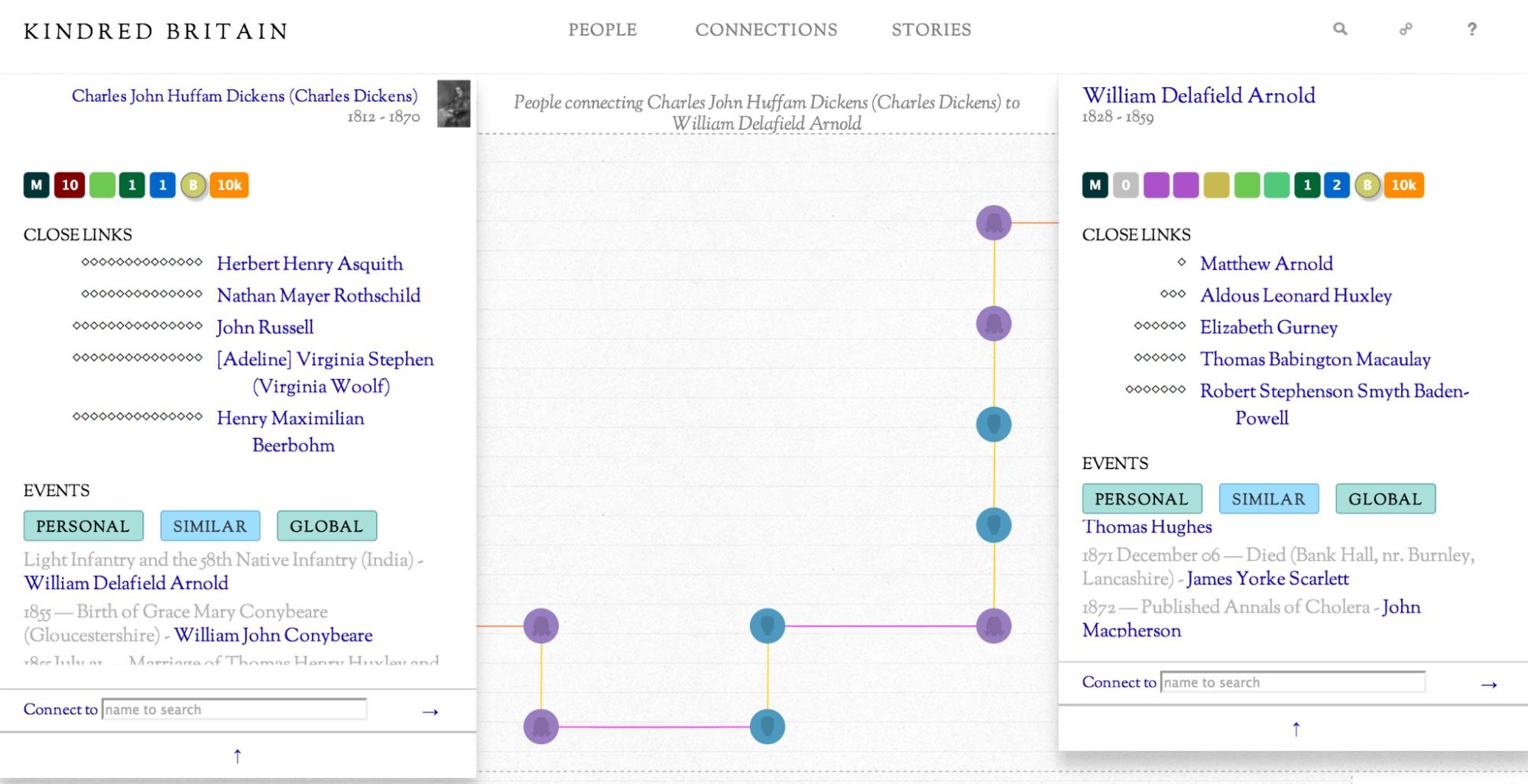

How do I see how two people are related?

Kindred Britain allows you to see the shortest path connecting two individuals. There are several ways to see these connections:

- In any view in the Network panel, you can drag one node (representing an individual in Kindred Britain) onto the top of another node.

- If you want to connect two specific individuals, use the Connections tab located in the Search dropdown.

- Each individual has a set of Close Links in his or her Biography Box or Card. These represent a selection of well-known people to whom they are more or less closely related. Click on one of these names to see that familial connection in the Network panel.

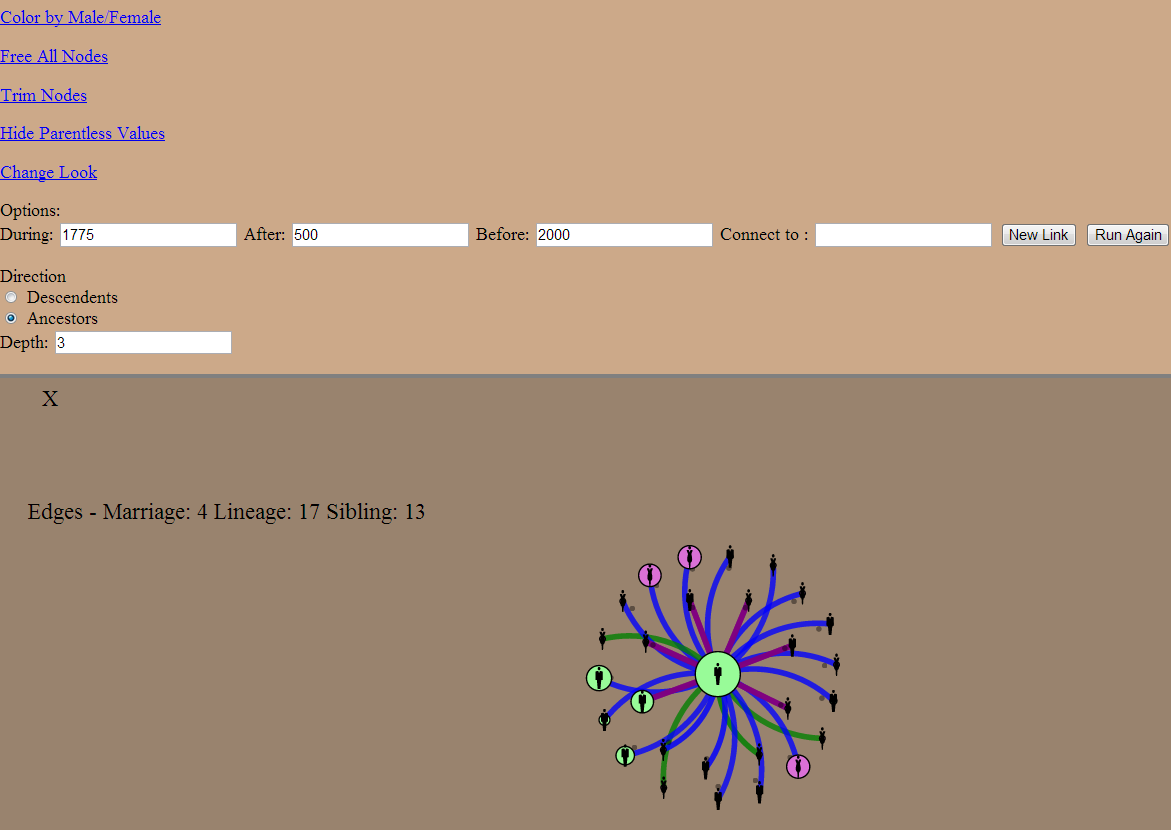

- Use the Connect To function, located at the bottom of the Biography Box and Biography Card, to connect the subject of the Biography Box to anyone else in the Kindred Britain network.

How do I start over?

You have two options. Using the Recent Views tab (located in the Search menu), you can navigate to any of the last five visualizations you viewed. If you want to begin browsing the site from scratch again, click on the Kindred Britain masthead in the top left corner and select the Start button in the dropdown.

How do I see if a particular person is included in Kindred Britain?

To see whether an individual and members of his or her family have been included in Kindred Britain, use the Search function, located in the top right hand corner of the page. To search for a particular person, use the Individuals tab; to search for families, use the Groups tab. If results are returned, click on the relevant name.

How do I navigate between the Network, Timeline and Geography panels?

The three panels have been designed so that you can view all three at once, any two at once, or simply focus on one. To open and close the panels, click on the label names on the right hand side. According to whatever the current view is, their number will increase or decrease (though at least one panel will always remain open).

What can I do with the Network Panel?

You can do a number of things to interact with a Network visualization. Hovering over a single node will identify who the individual is. Clicking on a node will open a Biography Card with a summary of the person’s life. You can also click and drag a node to interact with another node. If two nodes are connected, you can hover over the connections to see how different individuals are related to each other. Lastly, if you click the gear symbol on the Network label, you can apply a number of transformations to the visualization.

See also the Network Panel section of the User's Guide.

How do I know which individuals are currently displayed on the Network Panel?

To find a list of the names of people currently displayed, click on the title of the visualization. This is located above the Network Panel, and below the Main Menus. For example, if you are on the Welcome screen, click on the box titled ‘Some Luminaries in Kindred Britain’.

Content

Why didn’t I get the search result I was looking for?

Let’s make a rough estimate of the number of people who have lived in the British Isles over the last 1,450 years. If we put that number at 100 million and juxtapose it with the number of people in the Kindred Britain database, which is roughly 30,000, we see that the ratio of inclusion is tiny. It is not surprising to see how many people are not included. But, given this selectivity, it is striking to see how very many significant figures from British history are included.

That said, numerous famous names that you might be interested in are not returned when you perform a search. It is not impossible that a familial connection exists between one or all of these figures and someone already in the database. However, none has so far been established, and hence they are not - or not yet - part of Kindred Britain.

This isn't a complete genealogical record - why are certain family members left out of Kindred Britain?

The site does not attempt a procedure of complete coverage. In most cases, it does not list all members of any particular family. Instead, the effort has been to trace connections between selected individuals, usually on the basis of general historical or cultural interest. Over time, more individuals and material may be added, and corrections will be made whenever possible. As that happens, the interconnections between different parts of the database will increase. This site is a growing thing.

Moreover, Kindred Britain grew through a process that involved as much sensibility as rigor. The various boughs of the tree grew from branch to emerging branch as the compiler’s interests prompted them. Kindred Britain claims no kind of exhaustiveness of treatment. The main aim has been to make suggestive or interesting connections. We are always interested to hear from users about information which has not so far been included, but please be aware of the principle of selectivity at work here: while Kindred Britain is sympathetic to the desire for this or that fact or individual to be included, we are under no obligation to enter any specific detail or person into this database.

If you’re interested in learning more about the creation of Kindred Britain, see Nicholas Jenkins’ essay ‘Originating Kindred Britain’.

Isn’t everyone related to everyone else?

Not in a meaningful sense. Although recent scholarship claims that any two modern Europeans can ‘share around 2-12 genetic common ancestors from the last 1,500 years’,1 the identities of these ancestors and the relationships between them are rarely known. Kindred Britain fills this void by demonstrating that - for a certain stratum of British society - these ancestral relationships are far more immediate and densely interwoven than suggested. And the completely visible nature of these relationships in Kindred Britain reintroduces narrative and the specificity of personhood into the midst of an abstract scientific discourse.

Further, contemporary science, like traditional genealogy, remains focused on ancestry. This occludes the vast terrain of social relationships mediated by the institution of marriage. Kindred Britain incorporates ancestry, but it also goes far beyond it by embracing as well the crucial dimensions of familial connection and relatedness through marriage and other similar relationships.

1 Ralph and Coop, ‘The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe’, PLoS Biol, 2013.

How were the Timeline’s historical events picked?

The Timeline’s historical events are intended to provide a broader context for the lives of individuals and families in Kindred Britain. Year-by-year coverage runs from 1200 to 2012; due to the depleted historical record, the period before 1200 is covered much less systematically. Although it is impossible to compress any single year’s events into a text shorter than a single Tweet, the compilers have attempted to strike a balance between:

- providing basic historical information about British and European history.

- attention to synchronous developments in cultures across the globe.

- occasional picturesque, suggestive or unusual details that symbolize the presence of daily life in its randomness within the rigid chronological march of history.

Have I seen some of this site’s research somewhere else?

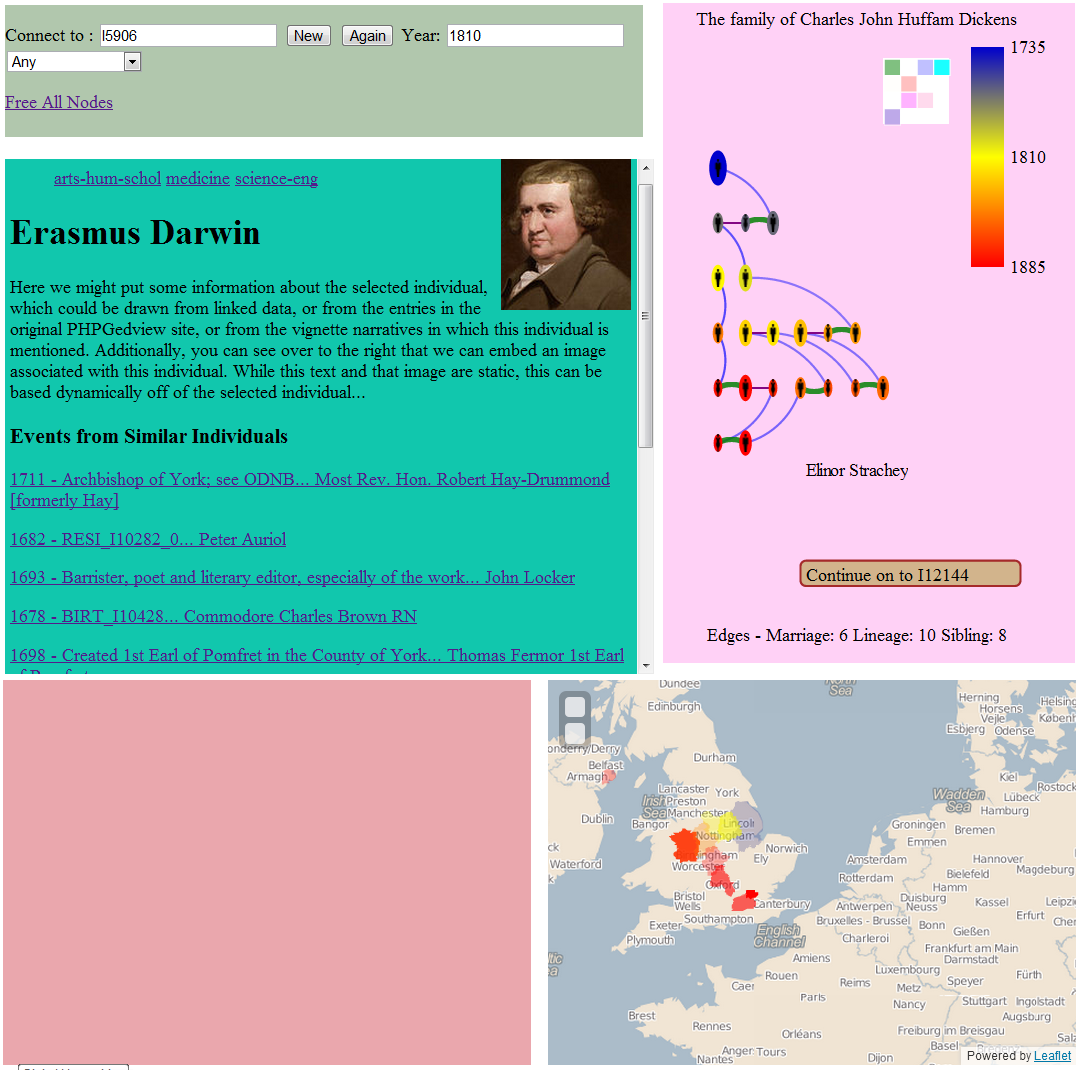

Nicholas Jenkins used a site called [W. H. Auden - ‘Family Ghosts’] (http://auden.stanford.edu) to compile an earlier version of this database. Though unlinked to and unadvertised, that site was visited by a number of users: it is possible that you first saw some of the material now exclusively on Kindred Britain in a different format there. Kindred Britain supersedes and renders superfluous W. H. Auden - ‘Family Ghosts’.

Can I add my research to the Kindred Britain site?

No. Kindred Britain is a standalone site, reflecting the best efforts of its makers to provide an image of British culture inflected through the lens of family ties. A mass of websites already exists for researchers who would like to share the fruits of their own inquiries with others.

However, Kindred Britain is always happy to receive corrections: click here if you would like to inform us about what you believe is an error, providing as much detail as possible along with your source references. We also welcome suggestions for future inclusions relevant to the overall research agenda of our site. But we regret that Kindred Britain cannot undertake research on your behalf nor is it obligated to enter into correspondence with you about matters such as genealogy, scholarship, British history, website design or any other subject.

Development

Who researched this? Who coded this? Who designed this?

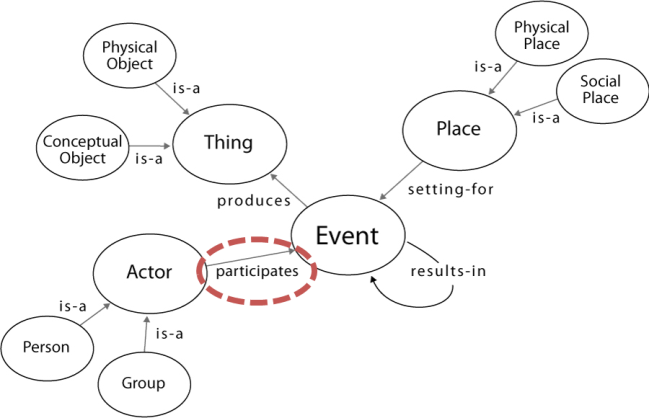

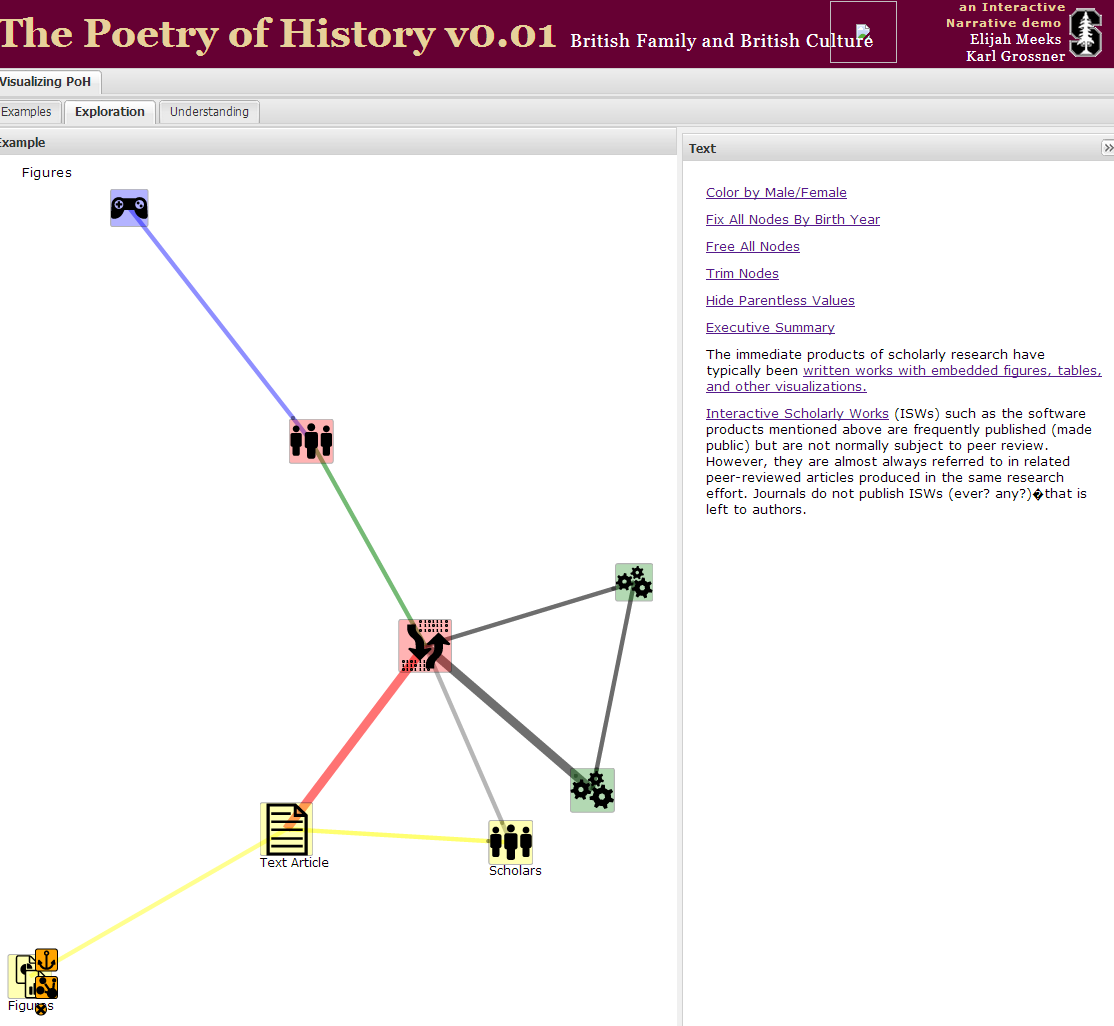

Nicholas Jenkins did the research presented on the site with help from Anthony Andrews and a number of other individuals who answered particular questions or provided specific information. You can read more about Jenkins’s work on the Kindred Britain project here. Elijah Meeks and Karl Grossner performed the software and database development on the site. You can read more about Meeks’s and Grossner’s contribution here. Scott Murray designed the site. You can read more about Murray’s contribution here.

Why was this site created? What is its purpose?

Inspired in part by Noel Annan’s epigram in his famous essay ‘The Intellectual Aristocracy’ that ‘Family connexions are part of the poetry of history’, this site was created to capitalize on contemporary developments in network theory and digital technology that have made it possible to show in new ways how intensely familial British culture and society have been. You can read more about the creation and purpose of the site in Nicholas Jenkins’s essay ‘Originating Kindred Britain’.

How did Kindred Britain come about?

In brief, Kindred Britain began as an individual research project conducted by a Stanford University English professor, Nicholas Jenkins, about family connections in British culture and history. You can read more about how Kindred Britain came into being in Jenkins’s essay ‘Originating Kindred Britain’.

In 2012, Jenkins had the chance to work with Stanford Libraries’ Digital Humanities Specialist Elijah Meeks on transforming the Kindred Britain database into a contemporary web-based format. You can read more about the coding and development of the site in Meeks’s and Karl Grossner’s essay ‘Developing Kindred Britain’.

Jenkins and Meeks approached the University of San Francisco designer and digital visualization specialist Scott Murray to join the project team. You can read more about the design of the site in Murray’s ‘Designing Kindred Britain’. The result is the site you are using.

Technical Issues

Why does my browser have trouble running Kindred Britain?

Kindred Britain takes advantage of advanced web technologies to display information using a variety of methods. This requires a browser that can display SVG (scalable vector graphics), and some browsers have better or worse performance displaying these graphics. Kindred Britain performs best in the Chrome browser, and should perform well in Safari and Opera. For reasons beyond Kindred Britain’s control, Firefox does not perform well with SVG graphics, and performance suffers as a result. With respect to Internet Explorer 9 and Internet Explorer 10 (beta), Kindred Britain simply does not work; if you are able to use another browser, we recommend you do so.

Some areas of the site aren’t visible on my laptop screen. What do I do?

If you are having trouble viewing Kindred Britain because of a small screen size, use the Control- or Command- key combination to zoom out, or click Zoom Out in the browser’s View menu. If this fails to help, click on the Kindred Britain masthead at the top left of the page and use the Start button to begin your exploration again.

Is there an app for Kindred Britain?

At this point, there is no Kindred Britain app.

Possible Errors and Further Questions

It says [X] was married five times, but I know it was only three. Is this a mistake?

Mistakes are always possible (indeed, in a work of this size they are inevitable) and, wherever and whenever feasible, Kindred Britain will correct them. If you believe you have found an error, or a bug, click here to report it.

Keep in mind that Kindred Britain uses experimental strategies and software in an attempt to produce some numerical summaries of a person’s life. One such technique is the ability to list the number of marriages an individual was part of. At Kindred Britain’s current state of evolution, we are not able to differentiate automatically between legally sanctioned marriages, long-term affairs or relationships, bigamous relationships and same-sex relationships. We hope, in the future, to refine our methods of articulating these connections. For now, Kindred Britain’s software errs in most cases on the side of inclusiveness in defining a number for the marriage badge.

I know that [X] was married and/or had children, but none of these relationships are listed. Why is that?

As noted above, the site does not attempt a procedure of complete coverage. In most cases, it does not list all members of any particular family, nor even any marriage for family members. Instead, the effort has been to trace connections between selected individuals, usually on the basis of general historical or cultural interest.

I want something added or removed from Kindred Britain. What do I do?

Every detail of this website has been compiled in good faith and with a belief in the accuracy of the information contained here. But we neither recommend making any practical decision of any sort based on what you read here, nor do we undertake to remove any factually accurate statements with which you happen to disagree or to add information which you desire to see included.

Why are there no sources, footnotes or references in Kindred Britain?

In common with many scholars of works about culture or history, the compiler of Kindred Britain made a conscious decision not to include references for the sake of retaining broad accessibility and legibility. This is a good faith effort made by an individual trained as a scholar. Mistakes have undoubtedly been made: in an exploratory effort of this kind, there can be no illusion of perfection. On the other hand, without exploration, there can be no possibility of extended knowledge or understanding.

I have a copyright concern. Whom should I contact?

Click here to send Kindred Britain details about your concern. Please be as specific as possible.

User's Guide

Contents

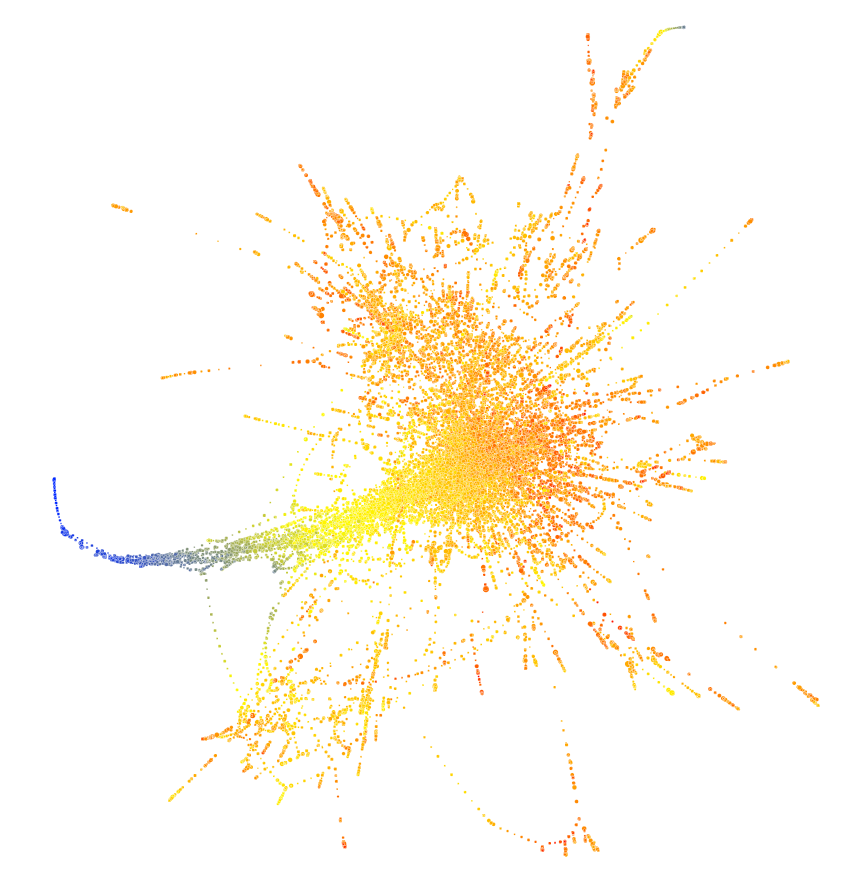

Overview

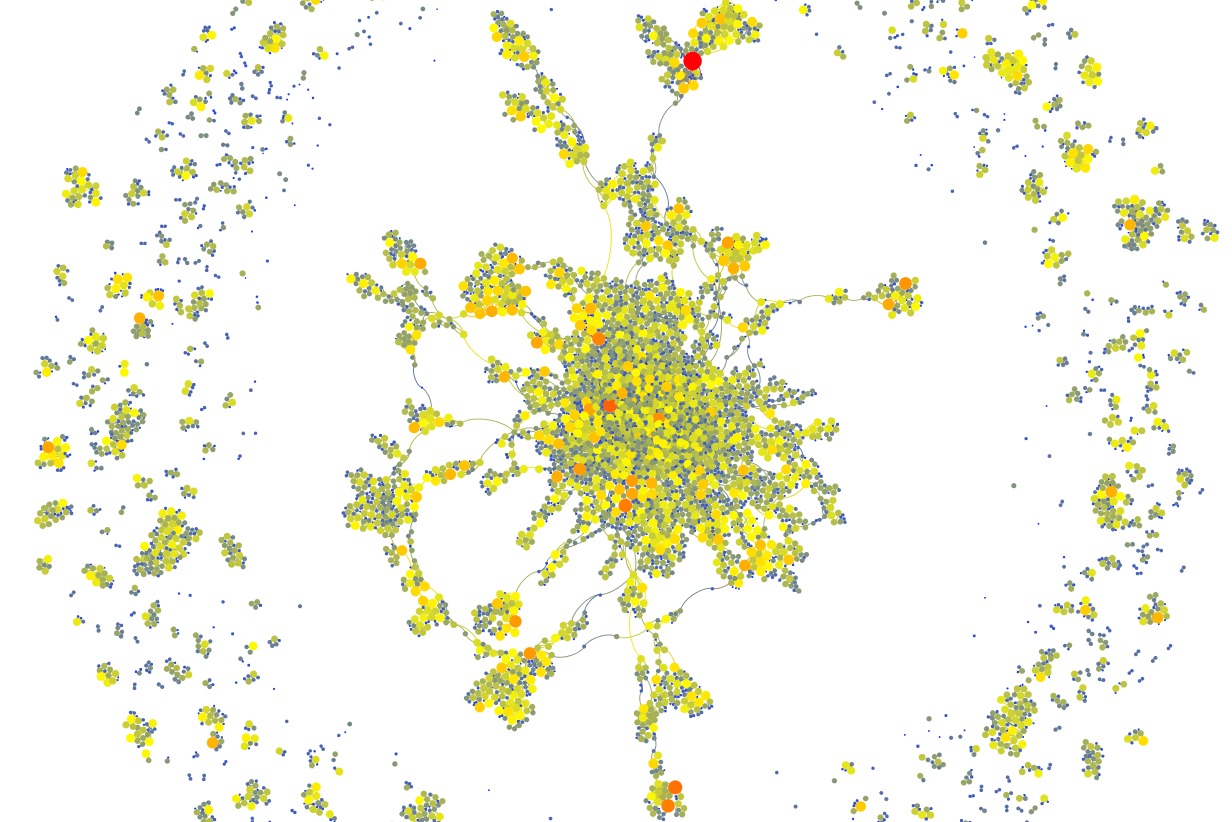

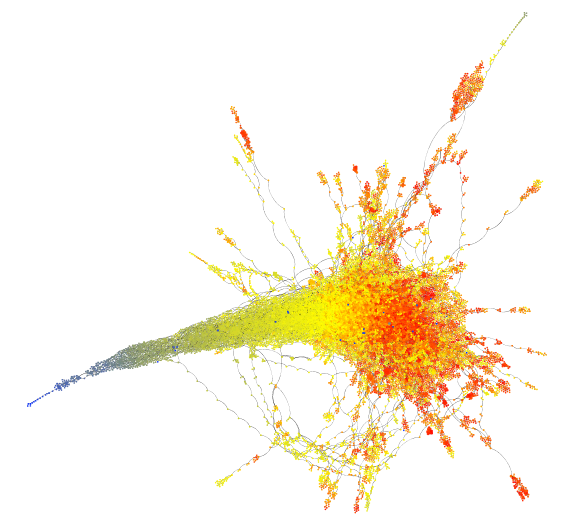

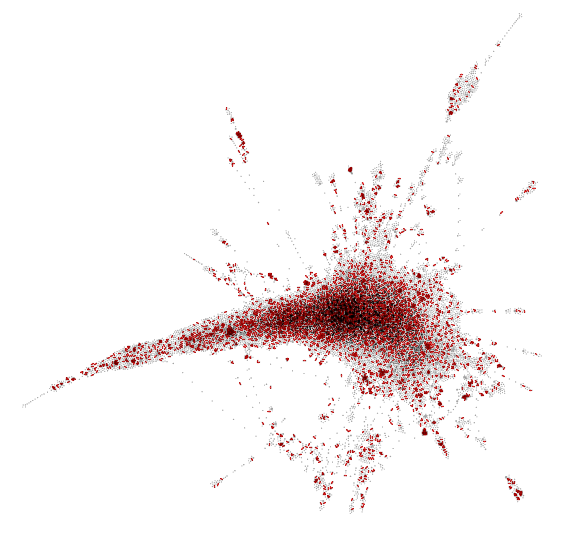

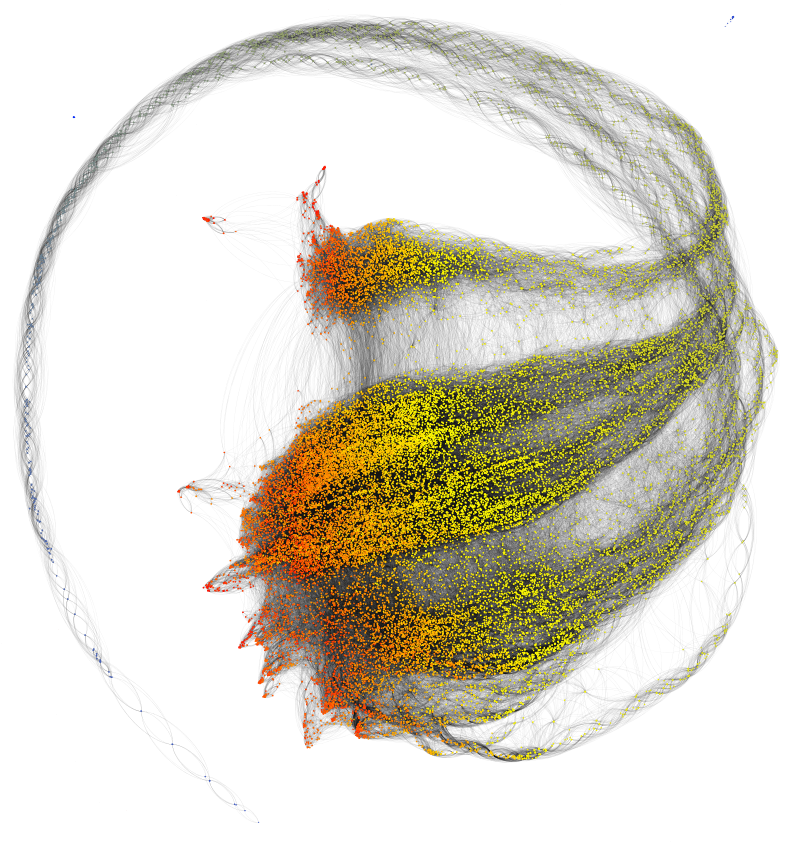

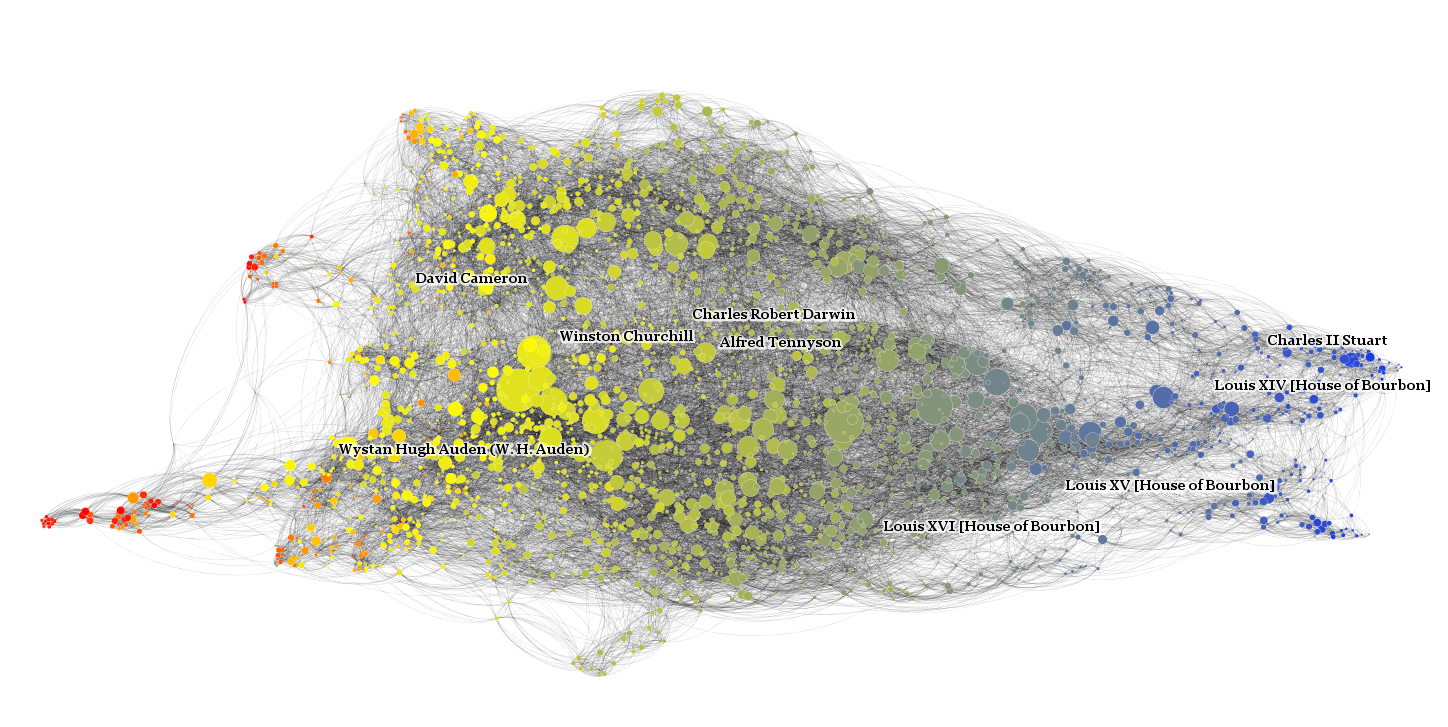

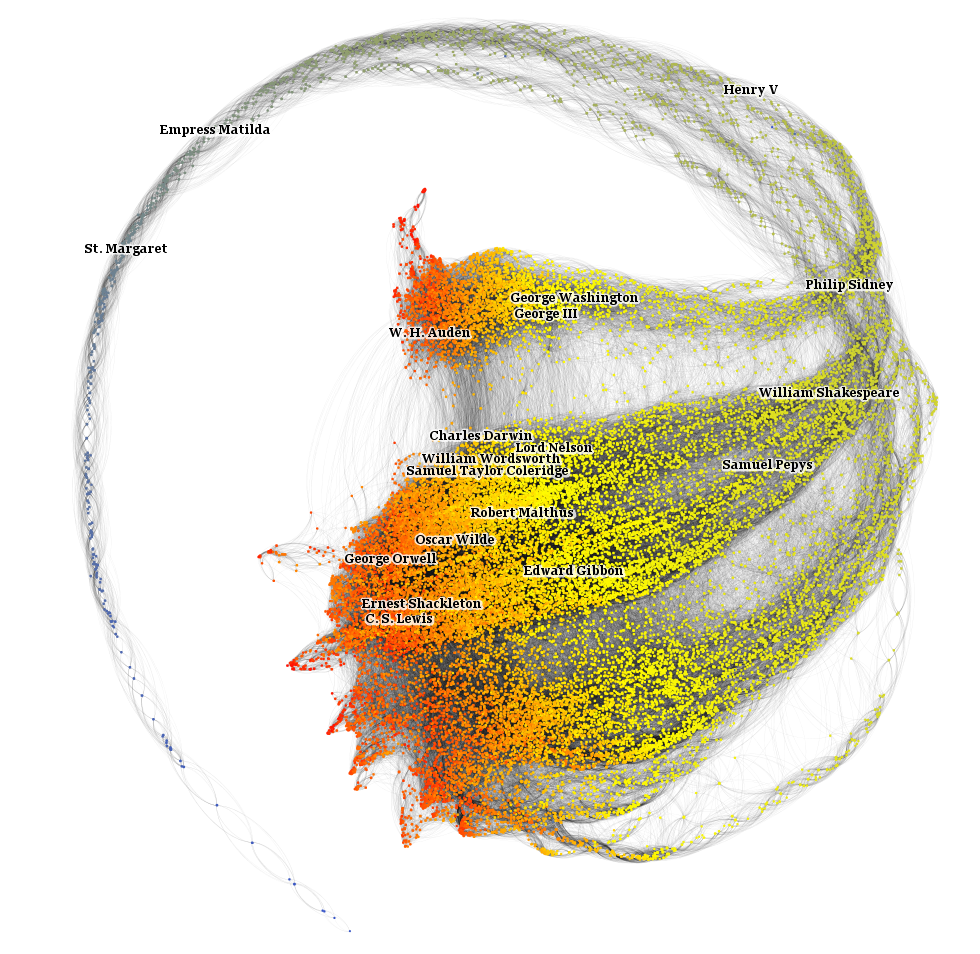

Kindred Britain is a network of nearly 30,000 people - mainly British, mainly dead - connected through family ties. But the site is not merely an extensive archival record. All sites, all datasets make arguments as well as presenting facts. Kindred Britain is a proposition about the profoundly and unusually familial nature of British society and culture.

If Kindred Britain were a book, it would be at least a foot wide and would weigh more than several bags of sugar. The material in it would be inert, static, and, because of its scope, virtually unassimilable. As it is, the data for Kindred Britain occupies a tiny, occluded space on one Stanford server. It glows on the wafer-thin silicon layer on your TFT-LCD display. And its contents are almost infinitely manipulable. Genealogy is one of the most ancient historical genres, and what was almost certainly the first self-conscious use of network understanding. Kindred Britain projects that old, conservative discipline into an absolutely modern medium to produce new understanding.

The effort embodied in Kindred Britain is multivalent. It is an intensive scholarly effort that also tries not to lose touch with the lightness, beauty and power of contemporary technology, nor to ignore that an intrinsic part of almost everyone’s online experience, high or low, is playful, popular, exploratory.

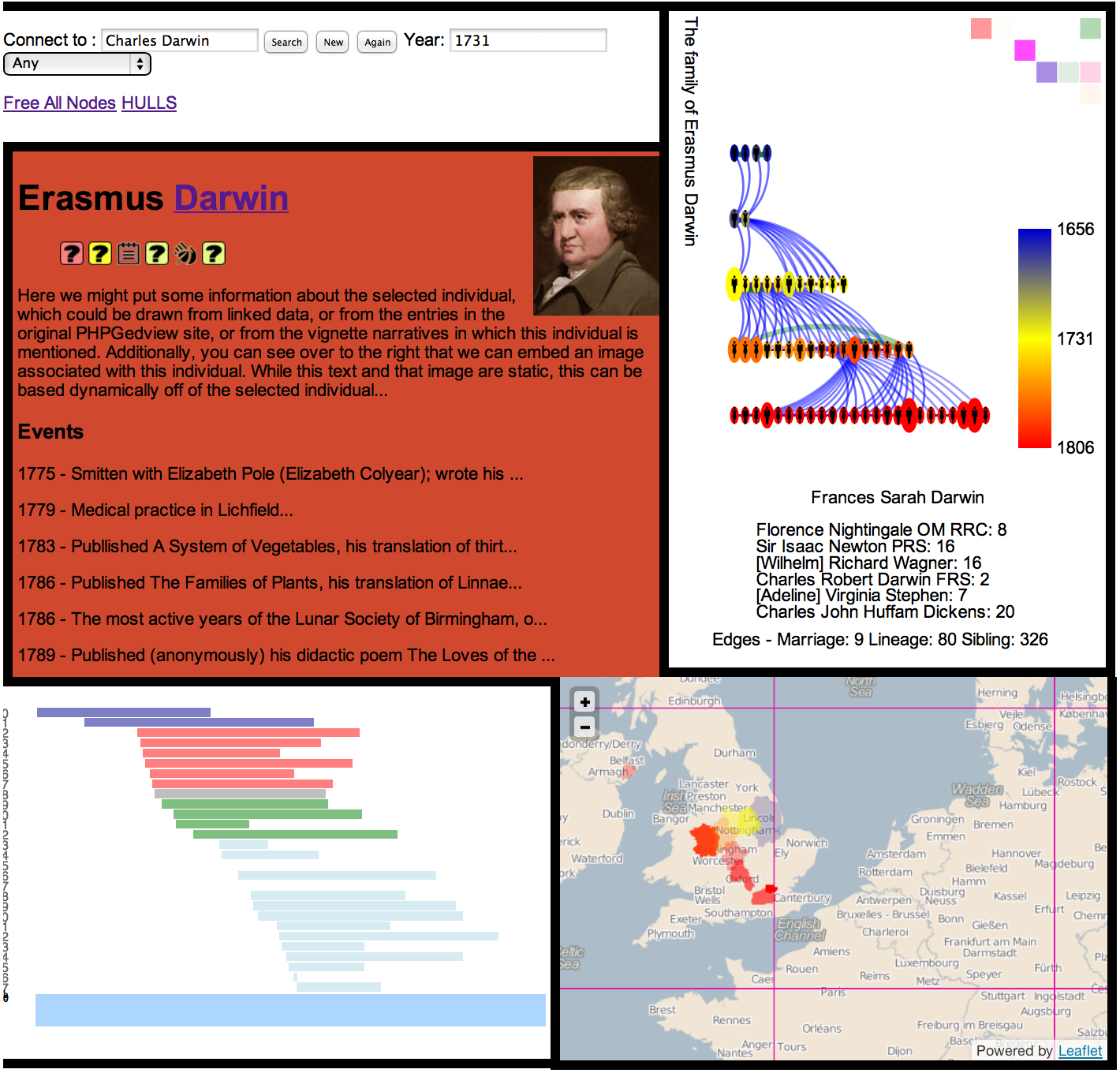

Kindred Britain is about relationships and connections. And, correspondingly, the three panel design (Network, Timeline, Geography) is constructed so that the site not only responds to the user but shows panels responding to what occurs in each other. In other words, the site is interactive both externally and internally.

One note: Kindred Britain is not intended to be a comprehensive biographical site. If you wish to find a narrative about an individual’s life, there are numerous online sources for you to draw, not least, in many cases, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). Kindred Britain does not try to duplicate information available elsewhere. Instead, it offers something unavailable elsewhere.

Three Modes of Engagement:

Play, Explore, Mine

It is impossible to read through Kindred Britain sequentially from beginning to end. It is a site to move around in either purposely or serendipitously, to return to for information or pleasure, to contemplate whether as a network or as a kind of image.

As this implies, you can interact with Kindred Britain in numerous ways. Here are three of the most basic.

- You can play, by dragging and dropping nodes on the Welcome screen. The drag and drop method of connecting nodes, which you first encounter on the Welcome screen, works on any visualization in the Network panel.

- You can go a bit further and explore using some of the curated connections and stories available through the Main Menu dropdowns.

- You can mine the deep interiors of the site using the search box. There are nearly 30,000 people in the site. That means there are over 870 million different paths through the Kindred Britain network. Use it for your research. Use it to suggest research topics. Use it to learn. Find out more about figures or families you already know something about. Or, through connecting someone familiar to a disparate sphere or world, reframe and reimagine an individual whom you think you already understand. The possibilities are virtually endless.

Kindred Britain’s hope is that these modes, which are not exhaustive, are also not exclusive. Thus, the spirit of play has been designed to inhabit the realm of research on this site, and the realm of play accommodates, perhaps even facilitates, the spirit of research.

Getting Started

Unless you clicked on a permalink in a Tweet, on a Facebook ‘Like’ or in a friend’s email, your first encounter with Kindred Britain probably comes through the Welcome screen.

Think of the Welcome screen as the starting point for Kindred Britain. This page is designed to help you become familiar with some of the tools that Kindred Britain has to offer. If at any point you wish to return to this page, click on the Kindred Britain masthead at the top left and choose ‘Start’.

On the Welcome page, the Timeline and Geography panels are minimized by default. In the Network panel, which is maximized, there is a small selection of nodes representing ‘luminaries’ from the Kindred Britain network. (These are by no means the only ‘luminaries’ in the site: for example, some 4,431 individuals in Kindred Britain also have an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. That amounts to around 8% of the total number of biographies in the entire reference work. In addition, there are eminent people still alive, at the time of writing, who therefore do not have an entry in the ODNB, as well as notable foreigners who are in the same position for a different reason.)

Hovering your cursor over a node identifies the individual represented by that node. Clicking on a node will cause a Biography Card to pop up with some information about the individual:

- Hover your cursor over the badges to see some statistical details of the individual’s life.

- Click on the picture (if there is one) to enlarge the individual’s portrait.

- Look at the ‘Close Links’ to other ‘luminaries’ in the network. If you like, click on a link to see the path connecting the two luminaries. Note: in this version of Kindred Britain, the path shown cannot be filtered or modified and will always be the shortest possible route between the two people involved.

- Get a brief description of the individual’s occupation.

For more on Biography Cards, see the section of that name below.

By dragging one node next to or on top of another, you can also explore Kindred Britain in two other ways:

- When the node’s blue penumbra turns orange, a comparison box will appear relating the two individuals in terms of historical time and differing lifespans. If there are any professional similarities, the box will also show these.

- When the node’s penumbra turns green, you can release your mouse button - doing so will prompt Kindred Britain to update the screen to show the familial path between the two individuals. From here, you can hover over any of the nodes and the lines between them to see how all the individuals on the screen relate to one another.

You can continue to explore some of what Kindred Britain has to offer by clicking, reading and perusing the rest of the site. Start your own search, or look at some of the curated material in the Main Menu dropdowns, or go back to the initial visualization on the Welcome screen to discover more connections. The world of Kindred Britain is at your fingertips.

‘Home’

Technically, Kindred Britain has no homepage. However, you can return to the Welcome Screen - which is similar to a homepage - at any point by clicking on the Kindred Britain masthead at the top left and clicking ‘Start’.

Site Architecture

Working with Panels

The overall architecture of the Kindred Britain site can be understood in terms of two sets of three. There are three independent but related panels - Network, Timeline, Geography - that provide three different views onto Kindred Britain’s data. The panels are where you see the results of your actions - and also where you can interact with the site through hovering your cursor, clicking and dragging. When you change the view in one panel or click on an element in another, the other two ‘kindred’ panels will respond to the action. (See each panel’s respective section for more information.)

You can view all three panels simultaneously, or any two, or just one. To open a minimized panel, click on its label name, located on the right; this will force any other open panels to share the available space. To close a panel, click on the label to minimize it. Note: the only time the panels will not respond to your mouse clicks is when you are looking at a single maximized panel and you try to minimize it. It is impossible for nothing to be showing on the screen. (See also Using Multiple Panels.)

Working with Dropdowns

The other main tripartite element is the set of clickable dropdowns: ‘Kindred Britain’ on the top left of the page, the Main Menus in the top center, and the Search, Sharing and Questions icons on the top right. These dropdowns allow you to look at different parts of the Kindred Britain database in a variety of ways. In essence, they are your primary method of exploring the site and issuing commands. You could compare them to three tunnel entrances all leading into the same mountain.

With the Main Menu dropdowns, you can simply click on the heading to reveal the dropdown. In many other areas of the site, you can open a panel or a box by clicking on the downward-facing arrow. To close a panel or a box, click on the upward-facing arrow. A right-facing arrow usually reveals more information or sends you to a new visualization or a new state of a box or dropdown menu, while a left-facing arrow closes the extra information or returns you to a previous state.

Tip: If you are accessing Kindred Britain on a smaller screen, it is possible you will not be able to see the up arrow that minimizes some dropdowns, panels and boxes. To remedy this situation, use the Control- or Command- key combination to zoom out, or click Zoom Out in the browser’s View menu. In the unlikely event that this fails to help, click on the Kindred Britain masthead at the top left of the page, select the ‘Start’ button and begin your exploration again.

Using the Network Panel

The Network Panel supports the crux of Kindred Britain’s argument. As Kindred Britain’s designer, Scott Murray, says, ‘Connections are the heart and soul of the site, as they represent what is unique about this historical data set’. You can take figures from highly disparate areas of British history and find family connections between them. The scientists connect to the artists and generals. The eminent Tudors connect to the eminent Victorians. The Network Panel allows you to learn about an almost infinite number of connections across time and through professional space. And it allows you to understand these connections visually rather than trying to absorb them verbally.

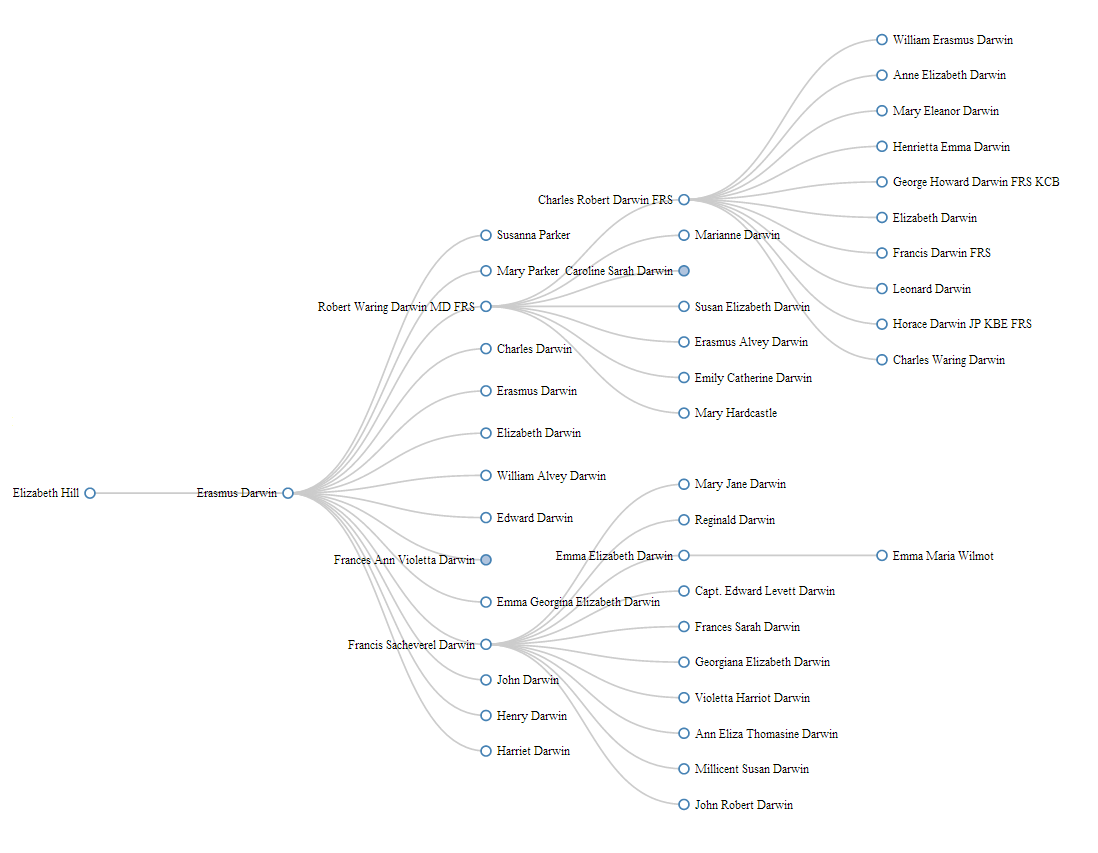

There are two types of visualizations. If you search for a single individual, the visualization will show his or her family tree. Otherwise, if you search for the connection between two individuals, the visualization will show the path of familial ties of marriage, lineage and siblinghood between the pair. The path shown cannot be filtered or modified, and will always be the shortest possible route between the two people involved.

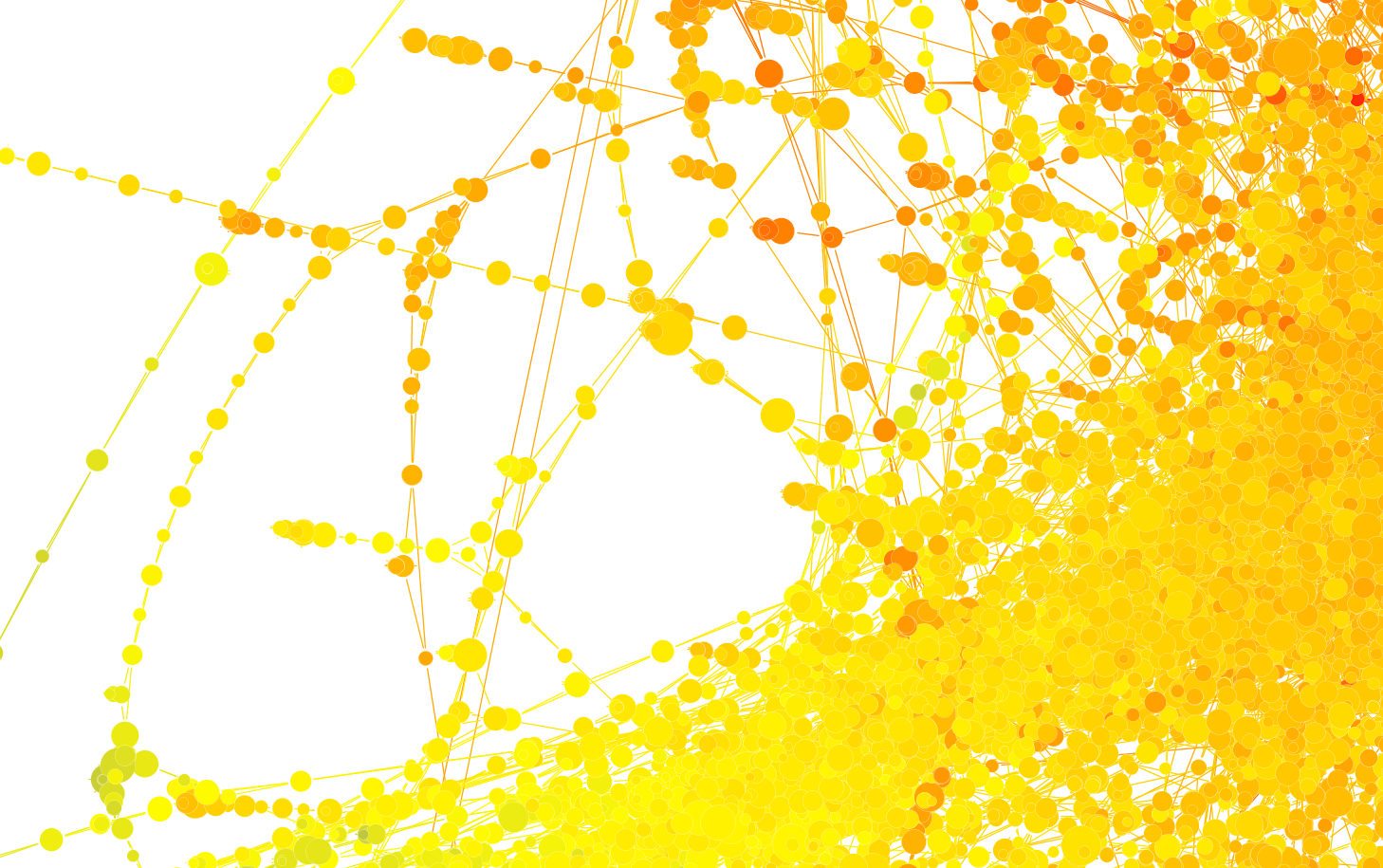

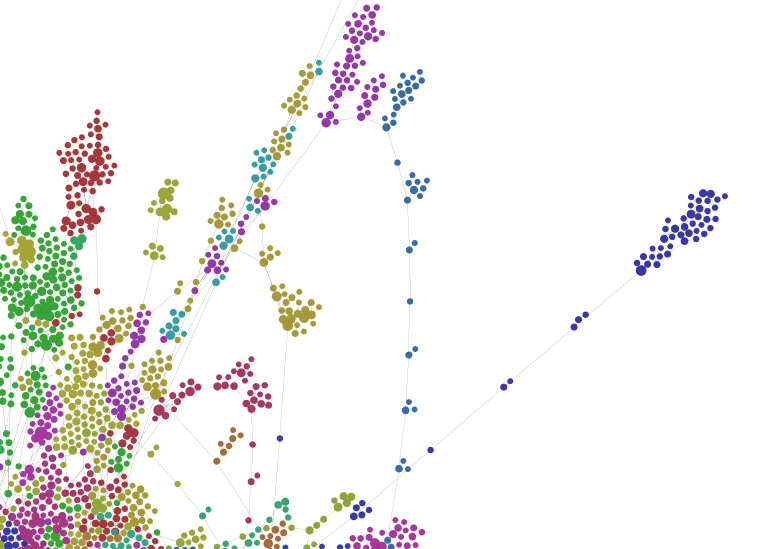

Whether you are viewing a family, a dynasty, or a familial path between two individuals, you can:

- View biographical information by clicking on any single node.

- Compare two nodes by dragging them closer until the surrounding circle, or penumbra, turns orange.

- Connect two nodes by dragging them on top of one another so that the penumbra is green.

To find the names of all the individuals currently shown in the Network panel, click on the Title dropdown in the middle of the page underneath the Main Menus. Clicking on any of the names will cause the screen to update: the new individual’s Biography Box will appear, minimized, on the left side of the page, and their family tree will populate the Network panel.

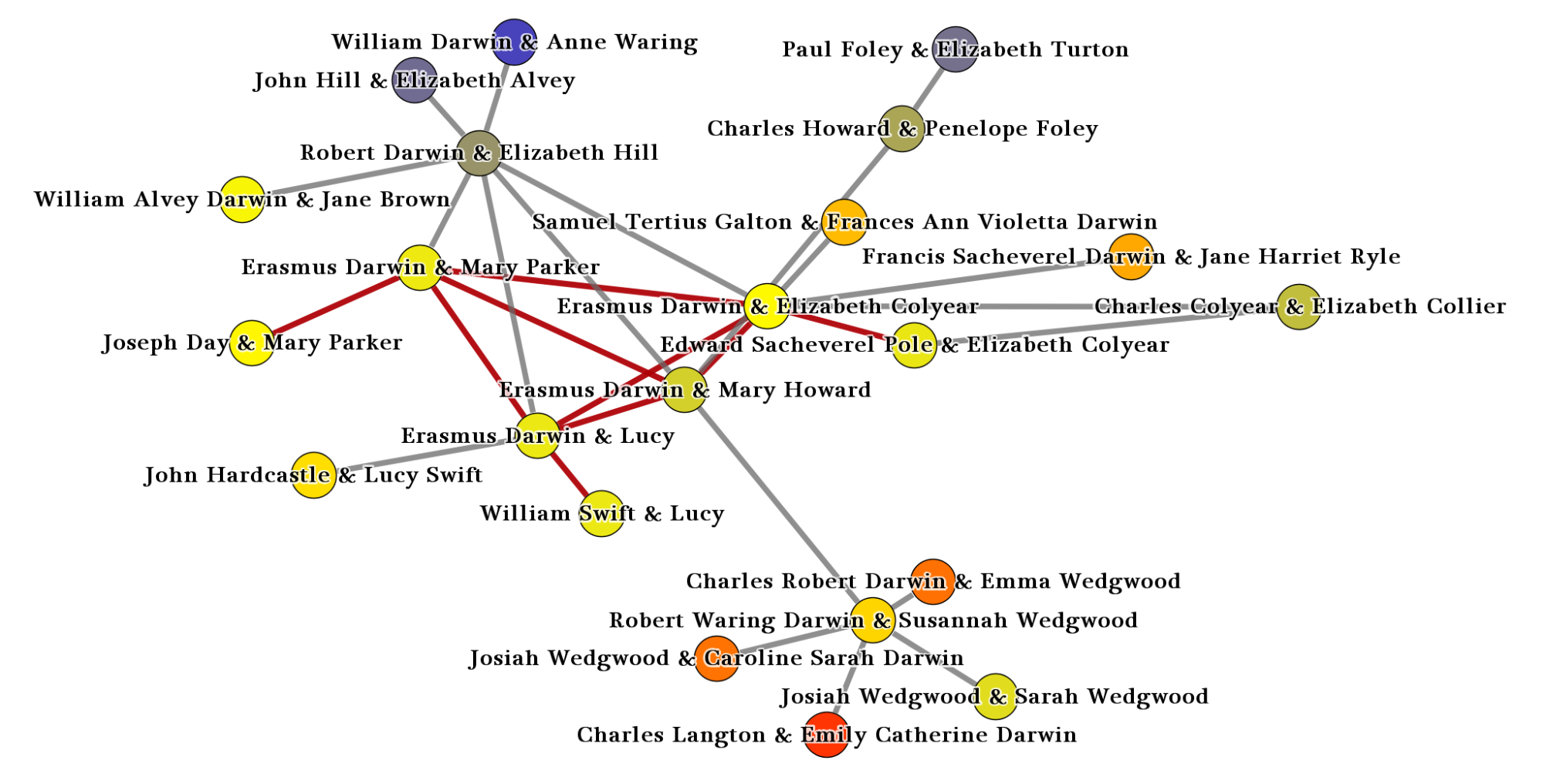

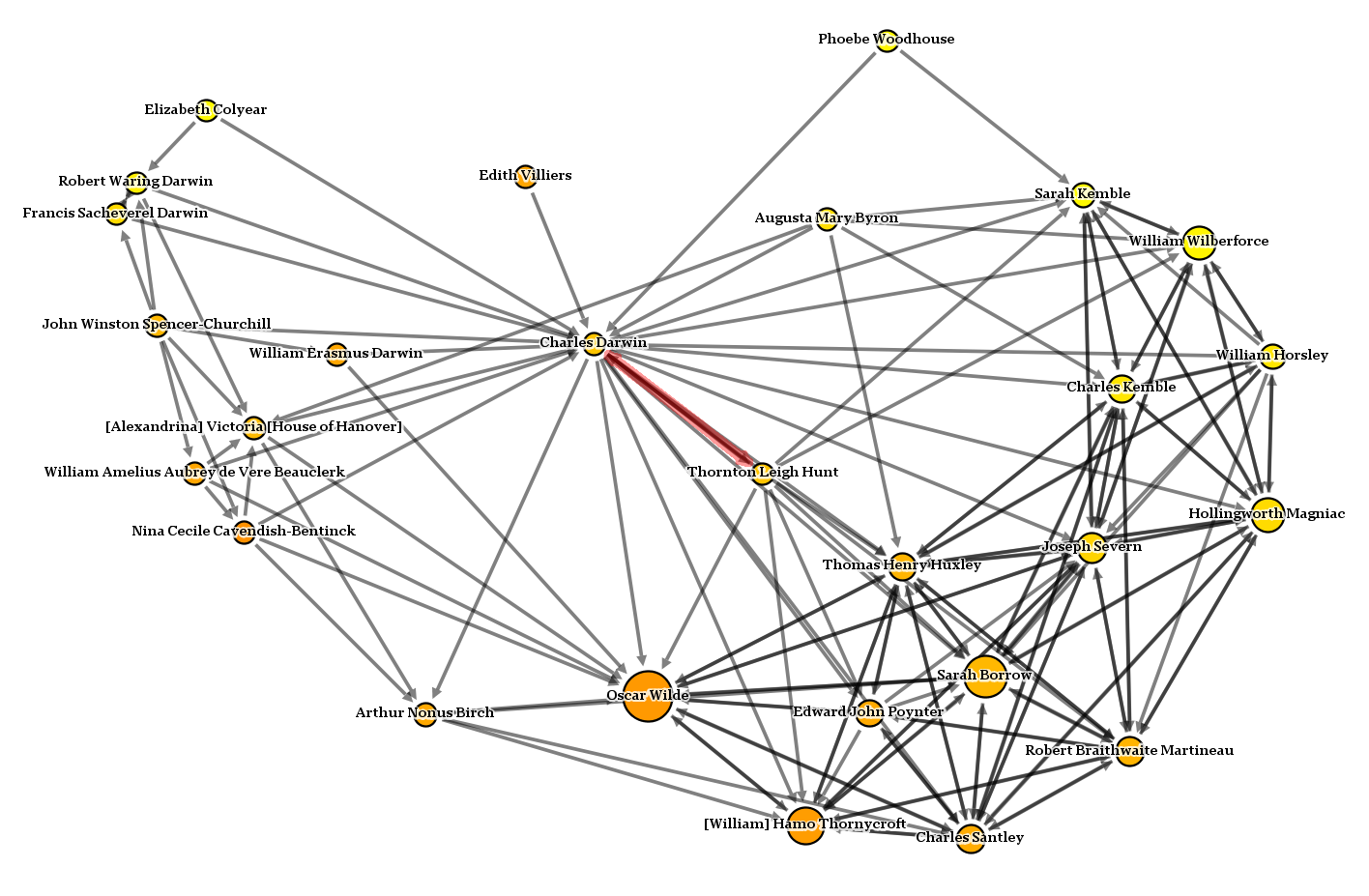

Reading a Network Visualization

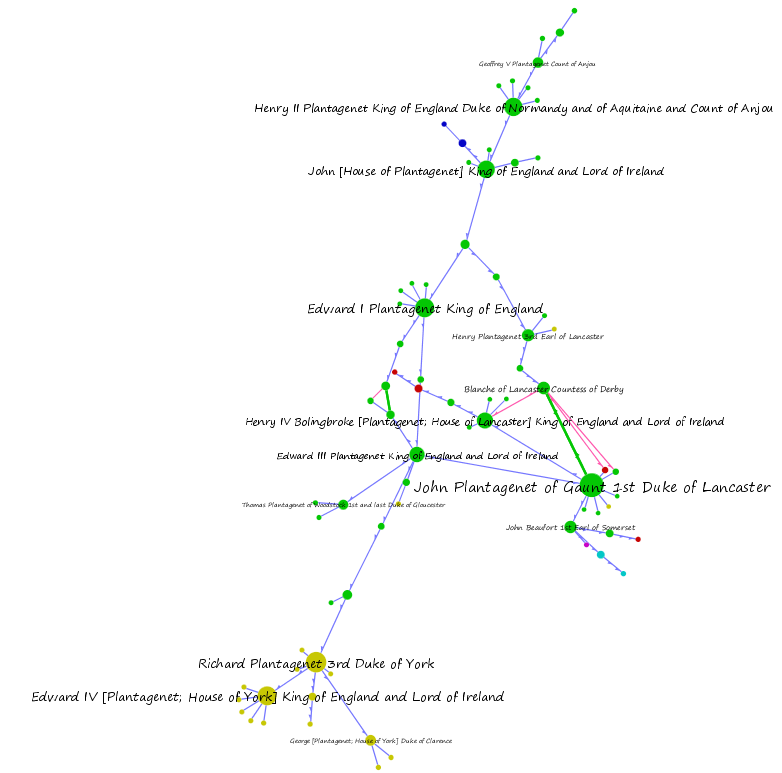

It’s easy to pull up a network visualization on Kindred Britain. And, with a little practice, reading that visualization is not hard either. Here are the ways that people can be connected to each other in Kindred Britain’s visualizations:

- A yellow line denotes lineage. For example, Elizabeth I is the daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, so a yellow line is drawn between her and each of her parents.

- A magenta line denotes marriages, domestic partnerships and affairs. If two nodes are connected to each other by a magenta line, then the individuals are related through marriage (most commonly), a partnership of some kind or by an affair.

- An orange line denotes siblings. If two nodes are connected to each other by an orange line, then the individuals are siblings.

Because Kindred Britain is designed around the current standard monitor size of 1200 x 800, if you are using a smaller screen, it may be difficult to see all the ways that people are connected to each other. If this is the case, you can click and drag the different nodes to different parts of the canvas so that it is easier to read the visualization. To reset the tree, open the Network Gearbox and select one of the available layout options.

Note that, in contrast to the actions in the Timeline and Geography panels, you cannot scroll up or down to zoom in and out in the Network panel.

To learn more about using the Network panel with the Timeline and Geography panels, see Using Multiple Panels.

Gearbox Transformations

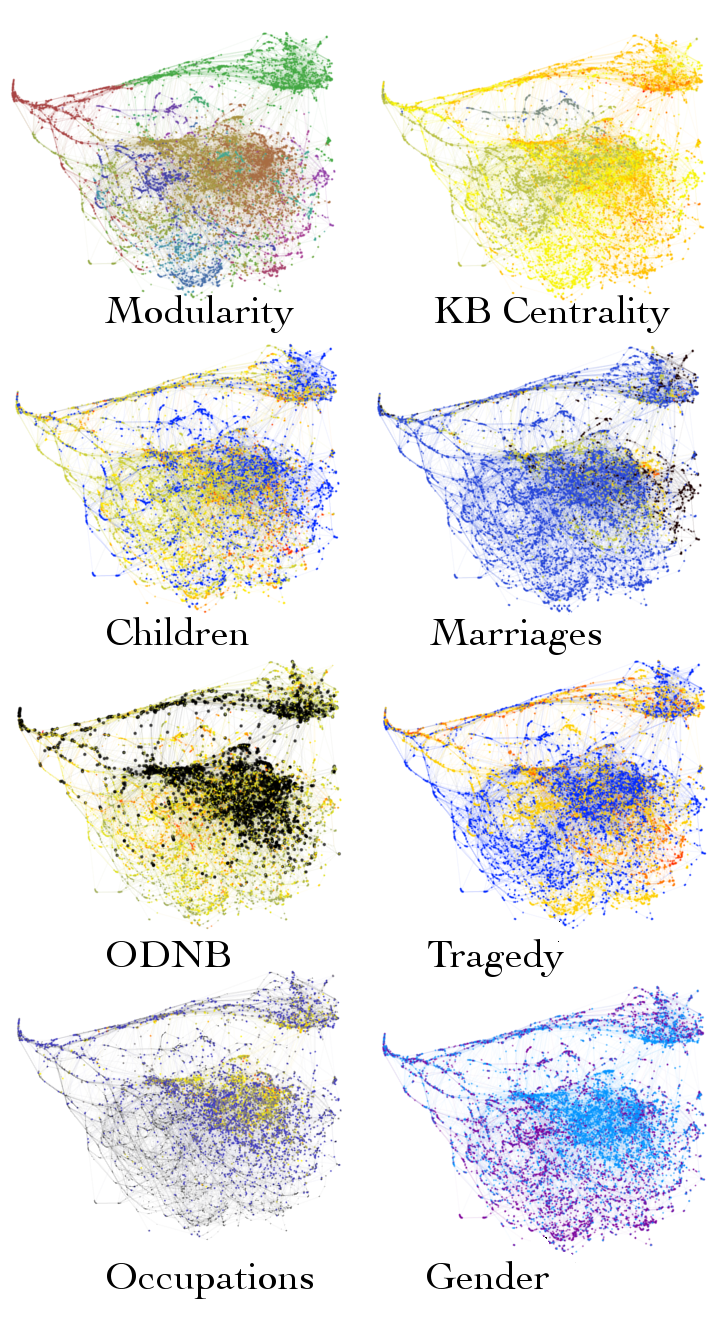

If you click on the Gearbox symbol located on the Network label to the right, you’ll see that there are two types of transformations you can apply to the currently displayed nodes. These are Layout transformations and Color transformations.

Layout

- The Tree layout creates a family tree for a family or a dynasty, and a grid for a connection between two individuals. This highlights the generations in a visualization. Note that this layout can only be used for networks in which all nodes are connected.

- The Plot layout plots the nodes on the canvas by Year of Birth and Year of Death. This gives you another way to view individuals on a chronological scale.

- The Force layout arranges the nodes according to a traditional force-directed algorithm. This means that nodes are attracted to the other nodes that they are connected to, and pushed away from nodes they are not connected to.

- The Professions layout turns on polygons (known as convex hulls) around nodes based on their occupations. This gives different approximations of social connectivity, to contrast with lineal connectivity. Note that the Professions layout is not available unless you are using a force-directed layout.

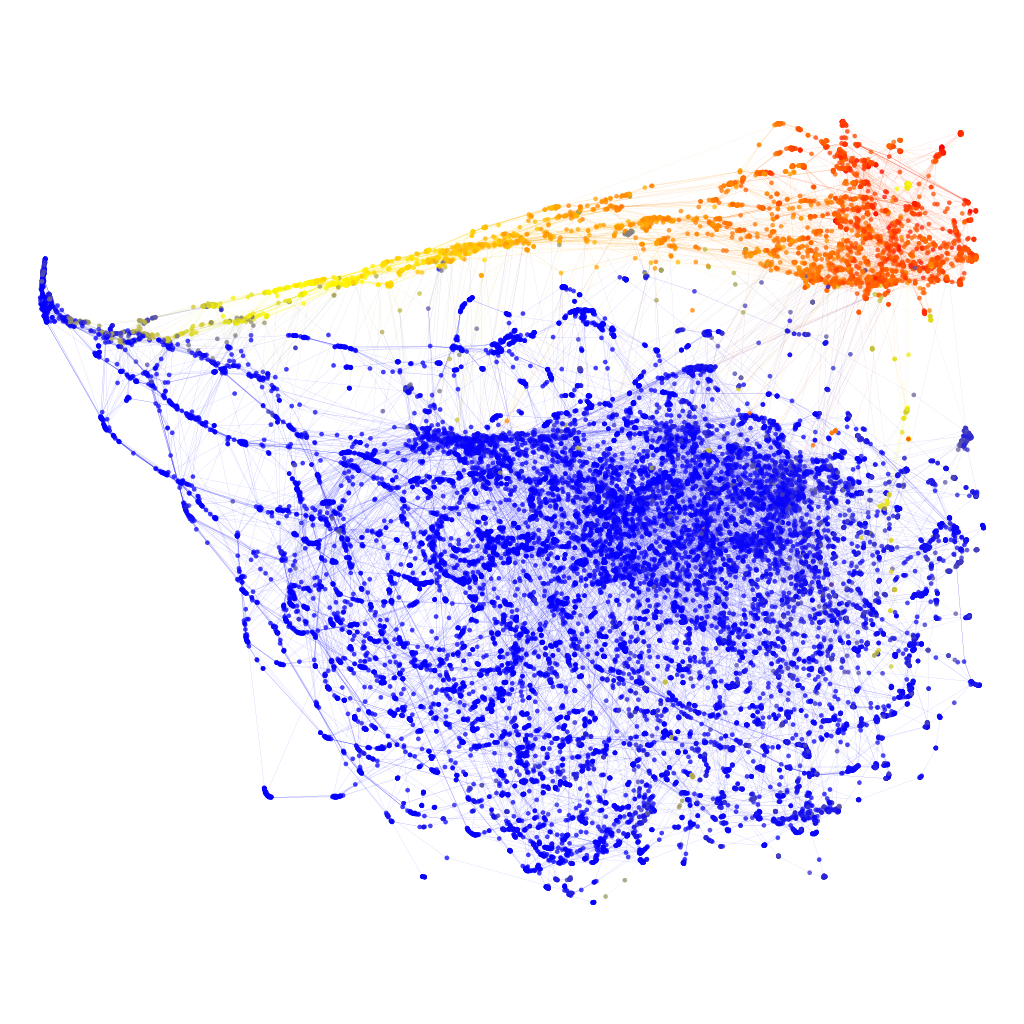

Color

- The Centrality function colors the nodes according to their centrality values, which is based on their level of connectedness in the network. See the conceptual story on Centrality for more information.

- The ODNB function colors the nodes by their ‘ODNB score’, which is the distance a particular node has from a relative mentioned in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

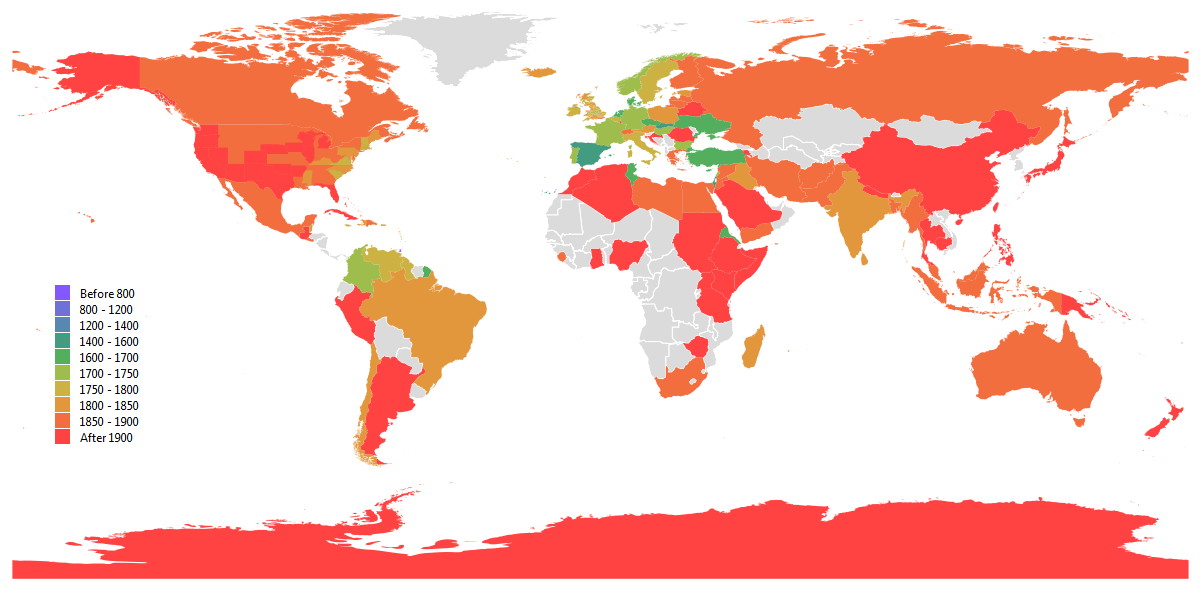

- The Birthdate function colors the nodes by year of birth.

- The Tragedy function colors the nodes by their tragedy score. See the conceptual story on Tragedy for more information.

- The Inbreeding function colors the nodes by their relatedness score. This quantifies about how many generations you need to go back in the database to find a common ancestor between the individual’s parents.

- The Depth function colors the nodes based on the number of ancestors mentioned in Kindred Britain. For example, an individual with a score of 40 has a lineage that can be traced back 40 generations in the database.

- The Gender function colors the nodes by gender. Male nodes are blue and female nodes are purple.

When you click on the different color transformations, a legend appears at the bottom of the Gearbox panel. This gives you a sense of what values correspond to what color on the screen.

Tip: If you have more than one panel open, you may not be able to see the color legend. To fix this, use the Control- or Command- key combination to zoom out, or click Zoom Out in the browser’s View menu. You can also minimize the other panels such that you have only one panel maximized.

Note that to close the Gearbox panel, you must click on the gear symbol itself.

Using the Timeline Panel

The Timeline panel takes the individuals currently displayed in the Network panel and lays their lives out on a timeline. The default setting is to view the lifespan bars in a Traditional layout. Here, you can hover over a single lifespan bar to view whichever events from an individual’s life are recorded in Kindred Britain.

As Kindred Britain is not a site for biographies, the events included on each individual’s lifespan bar are selective, rather than comprehensive. If you wish to learn more detail about the life of a particular individual, there are numerous online sources for you to consult.

Reading the Timeline

Blue circles, located throughout an individual’s lifespan bar, represent births and deaths; purple circles represent other types of events that took place during the individual’s life. For some visualizations, you may see vertical bars connecting certain lifespan bars. Green-gray bars represent a birth, and connect the blue circles of individuals involved with that birth. Purple bars represent marriages or domestic partnerships between two individuals, and connect their corresponding event circles. Divorces, which are also represented with a purple bar (these are another kind of marriage event), are distinguished by connecting gray circles from two people.

As you browse the Timeline, historical events will appear at the bottom of the panel to provide some context to the lifespan bars. This is a curated selection of events, and is not intended to offer a definitive account of history. It is designed to offer some juxtapositions between an individual’s life and a broader historical frame. (That is why the text in the historical events chronology is shown at a right angle to the orientation of the timelines.) To turn these events on or off, click anywhere in the white background canvas of the Timeline panel.

If you would like to examine the Timeline panel in further detail - especially if you are viewing a visualization with people who lived in multiple centuries - scroll up and down to zoom in and out.

To learn more about using the Timeline panel with the Network and Geography panels, see Using Multiple Panels.

Gearbox Transformations

Clicking on the Timeline gearbox allows you to color the lifespan bars according to different measurements - centrality, birthdate, relatedness, ODNB, tragedy, and depth - each of which is defined in the previous section.

One type of transformation unique to the Timeline panel is the Event view. In contrast to the Traditional layout, the Event view reduces the lifespan of each person on the panel to a single identifying event. A simple algorithm ranks the events of each individual’s life and attempts to display the most important event. The rankings are as follows, in descending importance: a story event (related to a narrative discussed in one of the curated Kindred Britain stories), a life event (for example, an invention or a publication), an occupation, a marriage, or a birth. Clicking on such an event expands that single lifespan bar, allowing you to view that person’s life in isolation.

Note that to close the Gearbox panel, you must click on the gear symbol itself.

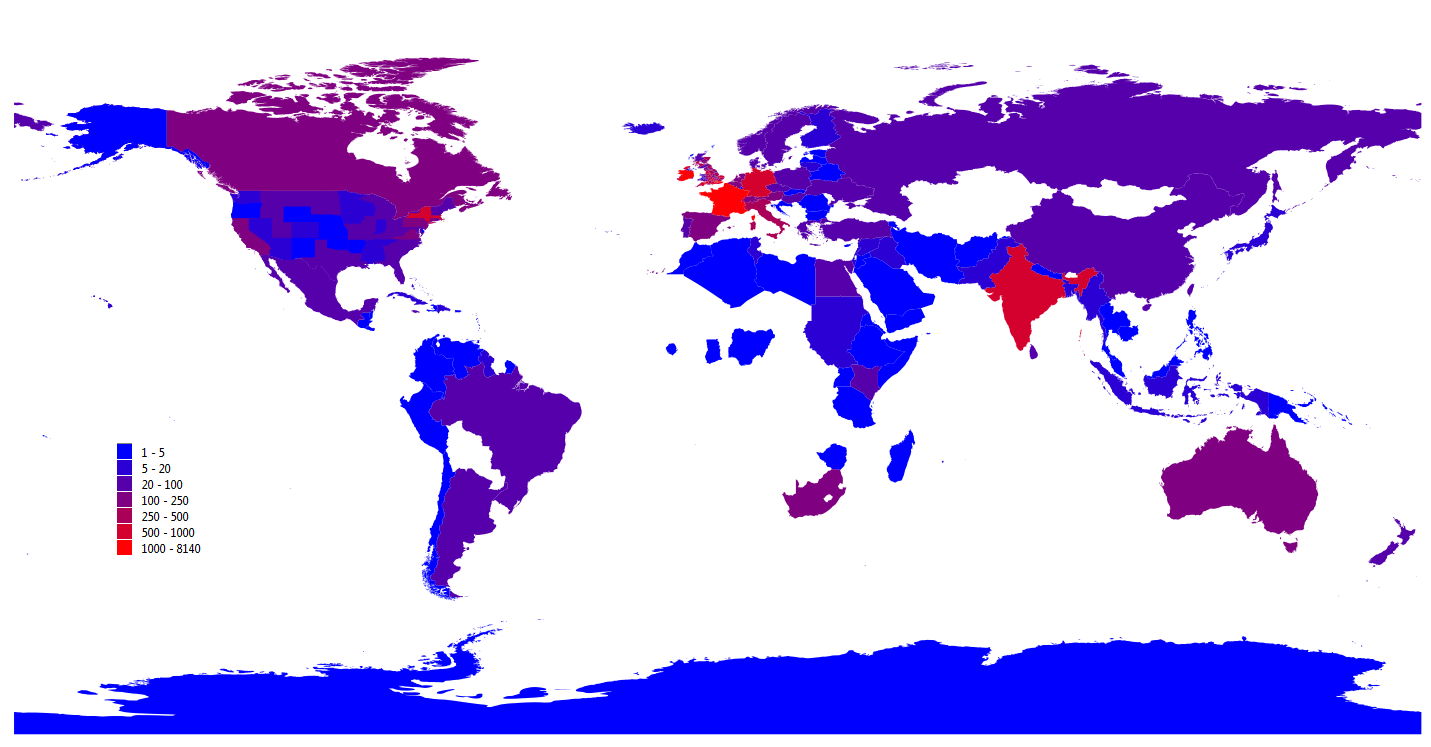

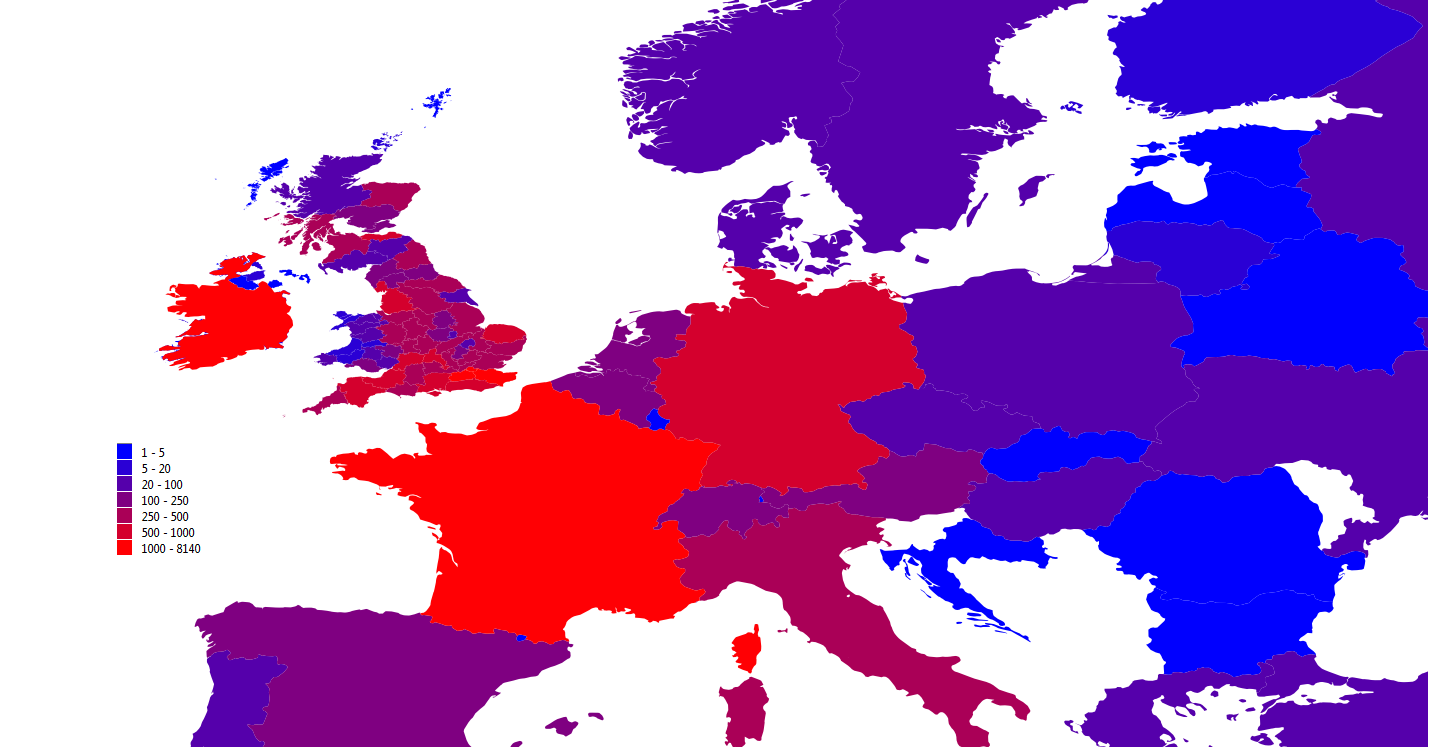

Using the Geography Panel

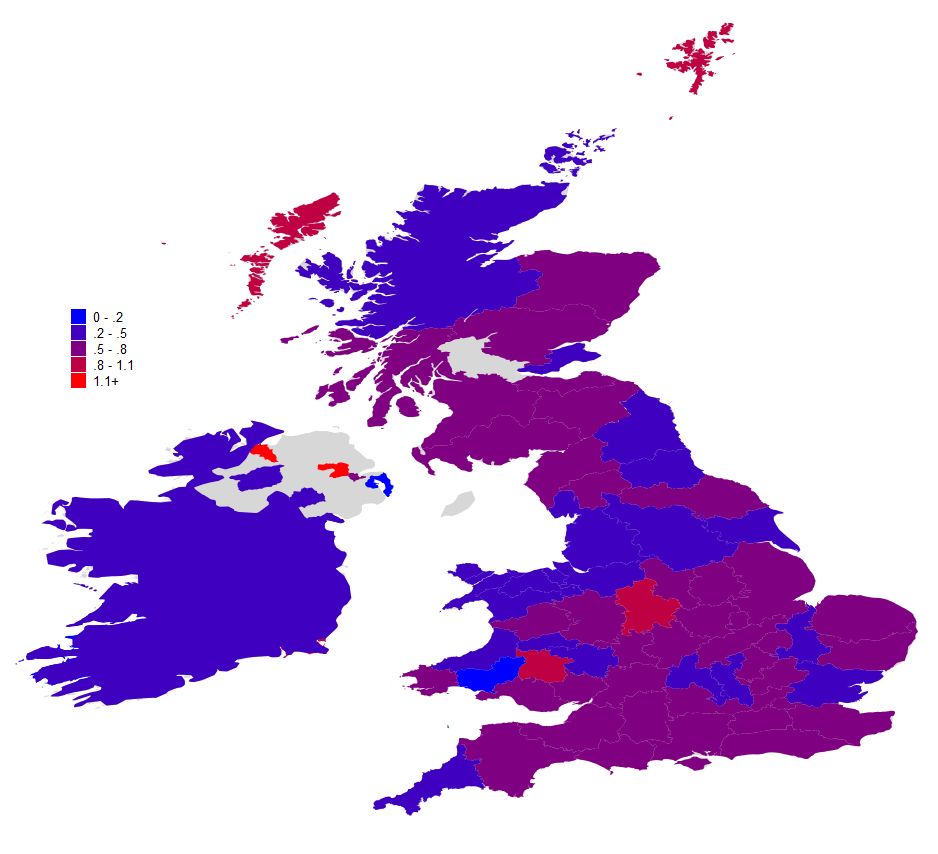

The Geography Panel provides you with a map of the world, with highlighted regions to denote the different places that the people of the current visualization are from. For example, if you open the Geography Panel while on the Welcome page, you can see that the selection of Kindred Britain’s featured ‘luminaries’ come, or came, from across Europe, Asia, and the United States.

Reading Geography

Hovering over a highlighted country or region allows you to see the people currently shown in the Network and Timeline panels who are associated with that place. In the current version of Kindred Britain, associations with a region are only included at the level of counties within Britain, states within the United States, and countries for the rest of the world.

If you would like to examine the Geography panel in more detail - a possibility especially likely in the case of England and its many counties - scroll up and down to zoom in and out.

To learn more about using the Geography panel with the Network and Timeline panels, see Using Multiple Panels.

Gearbox Transformations

Clicking on the Geography gearbox allows you to color the counties, states or countries of origin according to different measurements - centrality, birthdate, relatedness, ODNB, tragedy, and depth - each of which are defined in the Network Gearbox Transformations section.

One layout transformation unique to the Geography panel is the Cities layout. This function allows you to see the locations of some important cities across the world. Click on the button in the gearbox to toggle this function.

Note that to close the Gearbox panel, you must click on the gear symbol itself.

Using Multiple Panels

As described in the Working with Panels section, Kindred Britain allows you to compare the different types of visualizations next to each other. For example, having the Network and Geography panels open at the same time allows you to see where each individual in the visualization is from, if known. Or, if all three panels are open, when you click on a lifespan bar in the Timeline panel, the relevant node will be highlighted in the Network panel, and/or the counties and countries associated with that person will be highlighted in the Geography panel.

Opening and Closing Panels

To open or close the different panels, click on the labels ‘Network’, ‘Timeline’ or ‘Geography’. Note that you must click on the panel’s name on the label, not the panel’s gearbox. Clicking on a panel’s gearbox — which is located to the right of each panel’s name — allows you to perform transformations on the nodes. (See Network, Timeline and Geography.)

When a panel is visible, clicking on its label name on the right hand side of the page will minimize it. If a panel is minimized, clicking on the label name will enlarge it, forcing any other open panels to share the available space. If you want to look at only one panel, make sure the other two panels are minimized. Try minimizing and enlarging panels: the logic of the system is easy to learn.

Note: Kindred Britain, like nature, abhors a vacuum. The only time the panels will not respond to your mouse clicks is when you are looking at a single maximized panel and you try inadvertently to minimize it. It is impossible for nothing to be showing on the screen. At least one panel must be open while you are using the site.

Biography Boxes

If you search for an individual or the connection between two individuals, the left side of the page, and, if applicable, the right, will fill with a heading that gives the name, and birth and death dates for the individual or individuals you searched for. These headings are the minimized states of Kindred Britain’s Biography Boxes.

To open a Biography Box, click anywhere on the heading except for the individual’s name (this will direct you to the individual’s family tree) or picture (this expands the portrait). Once a Biography Box is opened, you can peruse a number of attributes, details and statistics, which has been presented in a condensed form akin to a character sheet in a role-playing video game (Experience, Abilities, Health, Items Possessed and so forth) - or, for the more traditionally inclined, akin to a player’s baseball card (Team, Biography, Number of Games, Runs and so forth).

Each Biography Box contains a number of features, depending on the level of information available and also relevance to an individual. The full range of features and their ordering is as follows:

- Name

- Dates of birth and death

- Portrait: If the individual has a portrait included in Kindred Britain, click on the picture to maximize and minimize it.

- Suffix: If the individual has a title (for example an earldom, a barony or a baronetcy), this will be shown here as will any post-nominal letters designating qualifications, positions, honours or memberships (for example, medals or memberships of the Royal Society or the Privy Council).

- Badges: Kindred Britain assigns, as applicable and according to what information is available in the site’s database, various coloured badges to individuals. From left to right, these are:

Married: Lists the number of marriages for this individual recorded in Kindred Britain. Not all marriages for every individual may be listed. The information given is circumscribed both by limits of available information and also by the selective nature of the database.

Note: Current limitations of Kindred Britain mean that sometimes socially recognized but not legally sanctioned relationships - such as ‘associations’ between male royalty and their mistresses - are described as ‘marriages’. Additionally, seeking to go beyond the hyper-traditionalism often implicit in genealogy, Kindred Britain selectively designates as ‘marriage’ some same-sex relationships.

Note that Kindred Britain is descriptive and not prescriptive. It does not claim to redefine ‘marriage’ as it has been understood throughout history. Rather, it tries to register some of the great variety of relationships which throughout history have together constituted the notions of kin and family. The designations made here are important but highly preliminary gestures towards better descriptions and understandings of what ‘family’ has meant in different historical contexts. Greater nuance in these areas is an important aspiration for subsequent versions of the Kindred Britain.

- Children Describes the number of children listed for this individual in the database. Not all children are listed, either because of limitations of the historical record or because of the selectivity of the database. Further details about the total number of children an individual had may be available in the Events section of the Biography Box.

- Professions: Awards a badge if the individual is known to have followed a particular profession. If the individual was active in more than one sphere or occupation, a number of badges are awarded.

- Tragedy Index: Attempts to signal the degree of ‘tragedy’ in the individual’s life. The algorithm for producing these values remains, to put it mildly, primitive. Nonetheless, to the creators of Kindred Britain, the effort to discern whether numbers can measure a subjective value such as ‘tragedy’ remains an important one and we invite users to reflect on this value in a speculative way. See ‘Computing Tragedy’ by Elijah Meeks for a lengthier discussion on the Tragedy Index.

- Generations of ancestors in Kindred Britain: Lists the number of generations between the individual and his or her most distant direct ancestor in the Kindred Britain database.

- Inbreeding: If an individual’s parents are related lineally, this score quantifies about how many generations you need to go back in the database to find the common ancestor.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography medallion: The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) is the standard biographical reference work for important figures in British history. Individuals who have an entry in the ODNB have a gold medallion in Kindred Britain. For those without, the medallion is blue, and the number in the centre indicates the number of steps or degrees this person is from someone who does have an entry. This medallion thus gives one rough indicator of social positioning.

- Centrality:Indicates the individual’s network centrality ranking, which is a technical measurement that does not necessarily correlate with historical significance. If the badge is orange, then that means the individual is in the Top [X] Most central (Top 10, Top 100, Top 1000, Top 10,000); if it is green, then he or she is in the Bottom [X] Least central (Bottom 10, Bottom 100, Bottom 1000, Bottom 10,000). If the badge displays an ‘M’, that means the individual occupies a position in the middle range and is neither particularly central nor particularly peripheral in network terms. This gives 9 categories of centrality, as represented in the Centrality Legend. See ‘Centrality and Notability in Genealogy’ by Elijah Meeks in the Stories section for a lengthier discussion on Centrality.

- Stories: If an individual is featured in, or relevant to, a story narrated in one of the site’s Stories, a link to that story will appear.

- Close Links: Shows the number of degrees of familial separation between the individual and five other figures of historic significance. Aside from showing connections between individuals who might not normally be linked together, Close Links also establish (as with the ODNB distance badge described above) a way of gauging relative social prominence.

This distance is measured in degrees of separation, with one degree being assigned for each step of distance. Thus a child is one degree or step from its parents as well as from its siblings or a wife is from a husband, just as a husband is two steps from his wife’s parents. Each degree of separation is represented by one diamond.

If you would like to connect this individual to any other person in the Kindred Britain database, you can use the ‘Connect To’ function at the bottom of the Biography Box.

- Events: Allows you to peruse whatever material exists in the database about the biographical and historical circumstances of an individual’s life. There are three filters: Personal, Similar and Global.

- The Personal setting, selected by default, shows selected events from an individual’s biography. The level of biographical coverage varies by individual and to some extent reflects the compiler’s sense of the ready availability (or lack) of information about an individual’s life. In cases where much precise information is readily available elsewhere, there is likely to be little on the Kindred Britain website. This setting can be switched off at any time.

- The Similar setting introduces events concerning contemporaries whom an algorithm suggests may be similar to the individual whose Biography Box you are reading. The measure of similarity is based on shared occupations, shared places, and similar numerical attributes derived from the system of badges described above. This setting is switched off by default, but can be switched on at any time.

- The Global setting introduces three historical events that provide context at three points of the individual’s life: the year of the birth, the middle of their lifespan, and the year of their death (if applicable). This setting is switched off by default, but can be switched on at any time.

- Connect To: The Close Links in the Biography Box give you an automatically generated set of historically significant figures to whom you can connect the individual. If you want to connect this individual to anyone else in the Kindred Britain database, use the Connect To search box at the bottom of the Biography Box. Once the terms of your search are established, the path between the individual you have been studying and your chosen second individual will propagate in the Network panel.

To close a Biography Box, click the up arrow at the foot of the Box.

Tip: If you are accessing Kindred Britain on a smaller screen, it is possible you will not be able to see the up arrow that minimizes the Biography Box. To fix this, use the Control- or Command- key combination to zoom out, or click Zoom Out in the browser’s View menu. In the unlikely event that this fails to help, click on the Kindred Britain masthead at the top left of the page and begin your exploration again.

Biography Cards

Biography cards appear when you click on a node in the Network visualization panel. These are essentially abbreviated versions of the Biography Boxes. Biography Cards feature Names, Dates of birth and (if applicable) death, Portraits (if included), Suffixes, Badges, Stories, Close Links, and a Connect To search, as well as a capsule descriptor (if available) of the person’s professional activities. You can always convert a Biography Card into a Biography Box by clicking on the individual’s name at the head of the card. See also the comments on Biography Cards in the Getting Started section of this Guide.

If you cannot see all the details in a Biography Box, you can drag the whole Network panel up until the details are raised into view. To shut a Biography Card, click the up arrow at the foot of the box.

Browsing Main Menus

In the top middle of the Kindred Britain page are three dropdown menus titled People, Connections and Stories. Each of these offers a way to browse some curated suggestions that will help broaden your understanding of the site, give you a sense of some of the possibilities to explore in Kindred Britain, as well as show you interesting and provocative historical vignettes.

People

The individuals in the People dropdown are a sampling of the thousands more you can explore for yourself in Kindred Britain. You can look at popular views, professional groups, famous families, well-known siblings, and individuals who formed some kind of historical landmark. You can create custom modified versions of these types of view, guided by your own interests, using the Groups tab in search.

Connections

Kindred Britain aspires to connects those normally unconnected to each other, such as those people divided by different fates. In the Connections dropdown, you can look at the familial ties underlying famous rivalries, judges and victims, poets and subjects, artists and sitters, doctors and patients, as well as those who lie next to one another in death. These juxtapositions illustrate just some of the connections between historical individuals that you can make on Kindred Britain.

Stories

Each of the Stories available through this dropdown menu is an in-depth curation of insights discovered using Kindred Britain. The Historical and Cultural stories focus on specific cases where using Kindred Britain has revealed something important or provocative — or just plain interesting — about a family or group of related people. The Conceptual stories explain some of the logic behind how the site is built — for example, how Kindred Britain computes an abstract quality such as ‘tragedy’, using life events.

A set of visualizations is pre-loaded for each Story. You can manipulate the visualizations as you can any visualizations with your mouse buttons and cursor or through using the various options in the Gearbox dropdown in any of the three panels.

If you decide to strike out on a novel path that your explorations suggests to you, rather than staying with the narrative line, you will navigate away from the story. If you subsequently decide you want to follow the story to its end, you can either re-select the story through the Stories dropdown or, if you had only recently been browsing through the narrative, you can return to it via Recent Views in the ‘Search’ dropdown on the top right of the Kindred Britain page.

Searching Kindred Britain

Search functions are signalled by the magnifying glass icon, which is the first of three icon on the top right hand side of the Kindred Britain page. There are four different ways you can perform searches in Kindred Britain: by Individuals, by Connections, by Groups, or by Recent Views.

To narrow your search, each of these search functions, except for Recent Views, uses a feature called a Birthdate Bar. By default, the Birthdate Bar is set to ‘Born anytime’. By dragging the left and right handles on the blue bar, you limit your search to individuals born within a particular time period. For example, searching for ‘Smith’ with the Birthdate Bar restricted to 1600-1700 will give you a much shorter list of results than searching for ‘Smith’, born anytime. To reset the Birthdate Bar to ‘Born anytime’, click on the white space of the blue bar.

In searches on the Individuals, Connections, and Groups tabs, the search function uses a basic weighting process - based on factors such as the individual’s historical significance and reputation - in an attempt to push individuals you are more likely to be searching for towards the top of your results. Because no possible matches are screened out, what the program deems to be less likely matches are ranked lower in the list of results.

Note: Search functionality is a complex issue, and the search functions in Kindred Britain are currently in an early stage of development. Searches in Kindred Britain are not case- or diacritical-sensitive. Additionally, this search finds results in the database with the name most similar to the query, and returns individuals associated with that query. For example, if you type in ‘Hampshire’, it will return anyone associated with the county Hampshire - not New Hampshire.

Individuals

Click on the Individuals tab in the Search dropdown. Type in the name of an individual into the text field to search for a person. Once the results have been retrieved, click on any of the names to go to a view of that person’s family, including all of their immediate relations who are included in the Kindred Britain database.

Tip: One way to search for individuals is to select a given period on the Birthdate Bar without typing any names into the text field. This gives you a list of all the individuals that are listed within a certain time period.

If you are unable to find a specific individual, this may be because of one of the following reasons:

- The database is selective, not exhaustive.

- The iron law for inclusion in Kindred Britain is that an individual have familial or marriage ties to someone already included.

- As this database was compiled by a single person, the individual was simply omitted because of whim, ignorance or choice.

Many historically significant individuals are not part of this network. However, it is part of the claim made by Kindred Britain that, rather than focus on the omissions, it is more important to focus on the fact that a surprisingly large number are included in this network. For the record, though, amongst those individuals not (or not yet) included are: the poets Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, the computer scientist Alan Turing, the playwright Ben Jonson, the scientist Michael Faraday and the fantasy novelist J. R. R. Tolkien.

Connections

If you have two specific individuals that you would like to connect, you can use the Connections Search to do so. Click on the Connections tab in the Search dropdown. The same basic procedures pertain here as for Individuals: Enter the name of the first person you want to connect and choose from the results. When the search box reappears, type in the second name you wish to search for. Either a list of search results will appear, or the panel will inform you that no matches were found for your search. If the latter happens, you can go back and try again. If the former, then click on a name to select it. Immediately after you click on the second name, Kindred Britain will lay out the familial path connecting the two individuals.

Groups

One powerful way to browse through Kindred Britain is by searching in the Groups tab. There are three ways you can search in this tab: by Profession, by Family and by Place. Click on the Groups tab in the Search dropdown.

Profession

The multi-colored boxes at the top of the dropdown box represent the different professions, or occupation spheres, held by the people of Kindred Britain. The default state of the Groups search tab has all Profession boxes disabled, so the color boxes are washed out. Hover over any Profession box to reveal its associated subpanel of specific occupations. Moving the mouse off of the profession box and/or its corresponding subpanel dismisses the subpanel. No click is required to dismiss the subpanel.

Clicking on a Profession box will select it, and therefore all of the various occupations listed on the subpanel. All of the colored boxes in the relevant occupation sphere will then become saturated. Clicking the Profession box again will deselect it, and therefore also all of its occupations. To search for certain occupations within a Profession, select or deselect your desired queries in the subpanel.

Family

Type in the name of a family to retrieve all the people associated with that family.

Location

Type in the name of a Place to retrieve a list of people associated in the Kindred Britain database with that location. In the current version of Kindred Britain, Location searches are only possible at the level of counties within Britain, states within the United States, and countries for the rest of the world.

You can perform a search using any combination of these filters. For example, you could use the Profession boxes to select ‘Poet’ and the Place search box to select ‘Devon’. Or you could input ‘Eliot’ in the Family search box and ‘Massachusetts’ in the Place search box. Or you could select Poet in the Professions box, input ‘Eliot’ in the Family search box, and ‘Missouri’ in the Place search box - this allows you to see all the poets in the database with the last name of Eliot who are associated with Missouri.

Recent Views

The architecture of Kindred Britain does not allow you to use your browser’s back button to browse through your previous searches. However, the Recent Views tab in the Search dropdown keeps track of the last five visualizations that you have viewed. Click on any of the listed visualizations to return to a recent point in your exploration of the site.

If you want to return to an earlier point in your use of Kindred Britain, the best option is to begin a new search on the person or family or path that you are interested in reviewing again. Or, if you want to begin completely from scratch, click on the Kindred Britain masthead on the top left of the Kindred Britain page and select ‘Start’.

Sharing Kindred Britain

You can share any interesting visualization you find on Kindred Britain in two ways: by the social media dropdown - via Twitter, Facebook, or Google+ - and/or by cutting and pasting the permalink from the Kindred Britain address bar into an email. However, for technical reasons note that some curated lists — such as the ‘Professions’ and the ‘Sisters’ lists in the People dropdown — cannot be shared with a permalink, and can only be accessed from the Main Menu. Explanations of how one may navigate to these curated lists are best made in words.

If you would like to cite Kindred Britain in a scholarly publication, there are a number of valid possibilities for doing so. Customs and norms are evolving in this area and we offer some provisional suggestions here. However, users with a preference for a particular scholarly citation style will probably want to adapt what follows to their own protocols.

If you are looking at a specific visualization on the site, we suggest you use the title of the visualization shown in the title area in the top center of the Kindred Britain page, together with the site name, the permalink associated with the visualization and the date accessed. For example:

‘The family of Ludwig Wittgenstein’, Kindred Britain, http://kindred.stanford.edu/#/kin/full/none/none/I28692// . Accessed 24 June 2013.

Some text on the site is available only in dropdown form with no permalink available, as is the case with the site description found under the Kindred Britain masthead under ‘Learn More’. We suggest citing such material in the following way:

Nicholas Jenkins, ‘Encountering Kindred Britain’ [masthead dropdown], Kindred Britain, http://kindred.stanford.edu. Accessed 24 June 2013.

Stories, on the other hand, can be cited with a title, part number, permalink, and accession date, thus:

Elijah Meeks, ‘Centrality and Notability in Genealogy, Kindred Britain, part 2, http://kindred.stanford.edu/#/story/third/third/third///centrality. Accessed 24 June 2013.

Material from anywhere on the ‘Notes on Kindred Britain’ sub-site, whether signed by an author or not, can be cited in similar ways. For example:

Scott Murray, ‘Designing Kindred Britain’,Notes on Kindred Britain, Kindred Britain, http://kindred.stanford.edu/notes.html?section=designing. Accessed 24 June 2013.

Or:

‘Frequently Asked Questions’, Notes on Kindred Britain, Kindred Britain, http://kindred.stanford.edu/notes.html?section=faq. Accessed 24 June 2013.

Notes on Kindred Britain

The About dropdown on the far top right of the Kindred Britain page is likely where you found the link to this User's Guide. The other material available in ‘Notes on Kindred Britain’ is a set of Essays by the three creators of the site, as well as a section of Statistics giving some numerical values and summations about the site. Also included are this User's Guide, a FAQs section, a Glossary and an Acknowledgements section. All this material can be printed out if the user desires. You can return to the main Kindred Britain site at any time by clicking on the button in the top right-hand corner of the screen.

Further Help

Kindred Britain is a complex site, and we have done our best to make this guide comprehensive. However, as has been stated elsewhere: ‘Omissions are inevitable.’ If you have looked through this User's Guide and have not found the help that you need, you can also consult the Frequently Asked Questions or the Glossary.

Glossary

GENERAL

Badges: Small, colored squares or circles in a person’s Biography Box or Card. Hovering over a badge with your cursor displays text explaining what the badge represents.

Biography Box: A summary of key points of an individual’s life. Appears as a heading anchored to the side of the screen when you view the individual’s family, or their connection to another person. Consists of a series of badges, a list of the individual’s close and famous relatives in the database, a one-line description of what the individual is best known for, and a list of Personal, Similar and Global events.

Biography Card: A brief summary of an individual’s life. Appears when you click on the individual’s node in a Network view. Provides a series of badges, a list of the individual’s close and famous relatives in the database, and a one-line description of the individual’s activities (if available).

Birthday Bar: Located at the bottom of each type of search - Individuals, Connections and Groups. Allows you to drag either side of the bar to select the range of birthdates that you would like to consider when searching for an individual. Set to ‘Born Anytime’ by default.

Close Links: Found in a Biography Box or Biography Card. A ‘Close Link’ is another notable person in Kindred Britain to whom the subject of the Box/Card is relatively closely related. Hover over the name of the Close Link to see how many degrees of familial separation exist between the subject and the Close Link.

Degrees: Used in determining Close Links. One degree represents one step of familial relationship. For example, a woman is one degree away from her mother or a brother, two degrees away from a grandparent and so on.

Diamond: Used in determining Close Links. One diamond indicates one degree of relationship distance between the subject of the Box/Card and the Close Link. More diamonds denote more degrees of distance between two people.

Drag and Drop: Interaction with computer where user places cursor over an onscreen object, clicks mouse button to ‘grab’ the underlying object, ‘drags’ the object across the screen by moving the cursor with the mouse button depressed and when the object reaches the desired location on the screen releases the mouse button to ‘drop’ the object in its new place.

Dropdown: Clicking on various buttons in Kindred Britain opens different menus of options. These menus are called dropdowns. For example, clicking on the title text in the top center of the screen (on the Welcome screen, ‘Some Luminaries in Kindred Britain’) will open a dropdown with a list of the individuals present in the current view.

Edge: Technical term in network theory for a line that connects two nodes. In Kindred Britain, edges represent relationships between nodes (people), such as those of ancestry, siblinghood and marriage.

Gearbox: Located on the top right corner of each panel, next to the panel’s name. Click on the gear icon to open a menu of options for modifying the color and layout for each panel.

Main Menus: The three menus located at the top center of the screen: People, Connections and Stories. People and Connections are a set of curated collections designed to give you a sense of some of the possibilities you can explore in Kindred Britain. The Stories menu guides a user towards interesting and provocative historical vignettes.

Masthead: Located in the top left corner of the site. Clicking on the Kindred Britain masthead will open a small menu with a brief description of the site. From here, ‘Start’ will take you to the site’s Welcome screen. ‘Learn More’ will guide you to a longer description of the site.

Node: A colored circle in the Network Panel, and a technical term in network theory for any object connected to other objects. In Kindred Britain, nodes represent people. Male nodes are blue, and female nodes are purple.

ONDB: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography - standard, multi-author reference work on the lives of important figures in British history. First volume published in 1885. It amounts (at the time of writing) to 58,664 biographies in 60 volumes in the print edition. The ODNB is also available online.

Panel: The Kindred Britain screen is divided into three horizontal sections. Each section is called a panel. The titles of the panels are available in the top right corner of each: Network, Timeline, and Geography. Panels can be active or minimized.

Profession Box: Located in the Groups tab of the Search function. Each Profession box represents a type of profession - for example, Politics or Law. Hovering over a Profession box brings up a subpanel, on which conceptually similar occupations within this profession are listed. These occupations can be selected or deselected to refine the terms for a search in Kindred Britain by profession.

Sub-site: Found by clicking the ‘?’ dropdown at the top right. This part of Kindred Britain, titled ‘Notes on Kindred Britain’, opens in a new browser tab. It contains general essays and statistics about the site, as well as various help resources including this Glossary.

Timeline Panel

Birth Bars: A type of shared event. Denoted by a green-gray vertical bar connecting blue circles. Connects all the people who are involved within a birth. Can be a mother-father-child combination, or just a parent-child combination.

Current Year Bar: Follows the cursor and shows what year the cursor is currently on. Also gives user a historical event to contextualize an individual’s life. This feature can be toggled on and off by clicking on the background to the Timeline.

Divorce Bars: A type of shared event. Denoted by a purple vertical bar connecting gray circles.

Event Nodes: Denoted by circles of various colors on a single person’s lifespan bar. Each of these nodes represents a notable event within that person’s life. Events represented are selective and not comprehensive.

Event View: Reduces the lifespan bar of each person on the timeline to a single identifying event. Clicking on an identifying event expands the lifespan bar of that individual.

Historical Events: Oriented perpendicularly to the lifespan bars on the Timeline Panel. These represent a selection of one or two events per year that give historical context to the lives of the individuals on display. Click on the background of the Timeline Panel to turn the historical events on and off.

Lifespan Bar: Horizontal bar that displays how long a person’s life is on a conventional timeline.

Marriage Bars: A type of shared event. Denoted by a purple vertical bar connecting purple circles. Connects two people in marriage.

Shared Event: An event that involves more than one individual. In Kindred Britain, this will be a vertical Marriage Bar, Birth Bar or Divorce Bar.

Traditional View: Displays the different lifespan bars in a conventional format.

Gearbox Transformations

Birthdate: Colors the nodes by Year of Birth.

Centrality: Colors the nodes according to their level of connectedness in the network. The most central individuals in the network are the most well-connected, which implies a certain level of influence or importance within the network. The overall network Centrality is calculated from a variety of different measures, including whether the individual is in the densest or most-traveled part of the network. For more information, see ‘Centrality and Nobility in Genealogy’.

Depth: Colors the nodes based on the number of ancestors discoverable in Kindred Britain. If we know 40 generations of ancestors for an individual, that individual will have a rating of 40, whereas if we can only go as far back as a grandparent, that individual will have a rating of 2.

Force: Lays the nodes out according to a traditional force-directed algorithm. Nodes are attracted to those nodes to which they are most closely related (those to which they have most connections or from which they have fewest degrees of separation). Nodes are pushed away from those nodes to which they are least related (those to which they have fewest connections or from which they have the largest degrees of separation).

Inbreeding: Colors the nodes by their Relatedness score, which is the number of generations you need to go back in the database to find a common ancestor between the individual’s parents.

ODNB: Colors the nodes by their ODNB score. This score is the distance from a relative mentioned in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

PlotPlot: Lays out the nodes on the canvas by Year of Birth and Year of Death. This gives you another way to view individuals on a chronological scale.

Professions: Turns on polygons around nodes based on their occupations. This gives some approximation of their social connectivity to contrast with familial (or lineal) connectivity.

Tragedy: Colors the nodes by their Tragedy Index score.

Tree: Creates a grid layout for a connection path, and a family tree for a family or dynasty. This highlights the generations of a family or path.

Biography Box, Biography Card

Centrality Badge: The network centrality ranking of the individual. If it’s orange, then that means the individual is in the Top [X] Most central (Top 10, Top 100, Top 1000, Top 10,000). If it’s green, then he or she is in the Bottom [X] Least central (Bottom 10, Bottom 100, Bottom 1000, Bottom 10,000). If it’s an ‘M’, then the individual is neither particularly central nor particularly peripheral. This gives 9 categories of centrality, as represented in the Centrality Legend.

Close Links: Some of the closest well-known historical figures. Their distance from the individual is represented by the number of diamonds.

Global Events: Lists three events that provide historical context to the individual’s life: one from the year of the person’s birth, one from the exact midpoint in their life and one from their year of death.

Inbreeding Badge: The ancestral distance between an individual’s parents, if they are related in the database.

Occupation: Indicates the occupations the individual had.

Personal Events: Lists (selectively) notable events that occurred during the person’s life.

Similar Events: Using an algorithm, experimentally lists events from other individuals in the database who are similar to the individual in the current biography panel.

Stories: Lists any stories on Kindred Britain where this individual is mentioned.

Tragedy Badge: A total of events in a person’s life defined as tragic and derived from the database: 1 point for dying young or to violence, 1 point for each child that dies before the age of 13, 1 point for each sibling that dies before the age of 13, 1 point for each parent that died during childhood, 1 point for each spouse that’s outlived by more than 20 years, and 1 point for mental illness. See the conceptual story on Tragedy.

Originating Kindred Britain

- E. M. Forster

Origins

In the beginning were the murders. Kindred Britain, a digital humanities project about the family in British history, was born in the distant aftermath of a set of domestic murders and a suicide. First came the deeds. Then, much later, came the words and the connections.

In early 1908, my great-great grandfather, Frederick Holmes, was a businessman living with his family in the hamlet of Fawley in Buckinghamshire, by the gentle meanderings of the River Thames. It was Wind in the Willows country. A brewer, Frederick had made and lost a great deal of money and, by the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, he had also become ill with a series of grim but unspecified ailments. His eyes were failing, he kept losing his balance, he had ‘gastric pains’. The family kept up appearances but their world was under pressure. He still tramped the fields with friends, shooting at creatures. But he had been forced to sell his last horse. Then, one night in February 1908, Frederick got up in the darkness of his bedroom, loaded his Webley revolver and shot my great-great grandmother Florence where she slept. He then moved down the corridor and shot their sleeping daughter Winifred. Afterwards, he climbed to the attic and murdered the young servants Lizzie Hayes and Ethel Morris. Frederick returned to his bedroom and, next to his wife’s corpse, reloaded his revolver before moving downstairs and out into the English countryside. A white, winter sun must have been coming up, there must have been heavy dew on the ground, birds must have been singing. He wandered around for several hours in who knows what agony of spirit before taking the gentleman’s (or the madman’s) way out and turning the gun on himself. A newspaper reported that Frederick’s body was found later ‘lying face downwards among the long grass and weeds. Blood was on the grass, near at hand was the weapon, and a brief examination showed that he had shot himself through the heart.’

Over time, that corpse became the skeleton in the family closet: never mentioned, let alone discussed. It was a loud silence, like the moment after a bang, in the background to everything. But, by accident, in 2007 I found out about the deeds that this enigmatic, deeply disturbed relative had carried out. It was hard to know how to react, how to feel: the story seemed about something far off and yet very close. Perplexed, I tried to piece the facts together in a blog entry called ‘The Events at Henley’. But I could offer no explanation and, even though the inquest was reported in the Times, some of the basic details were hard to establish. I thought it would end there: let the dead bury their dead. Not long afterwards, though, I received an email from Anthony Andrews. A retired British army officer, Anthony specialized in genealogical research, a subject I then knew nothing about, but which I have since learned constitutes one of the largest communities of investigators on the Internet. Genealogical sites on the Internet such as Ancestry.com are now so large that they advertise for customers on old-style media like television.